Columns

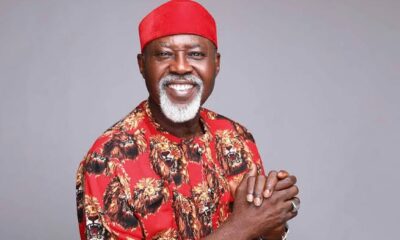

Brigadiers Benjamin Adekunle and Foluso Sotomi Suspended Amid Hemp Smuggling Allegations

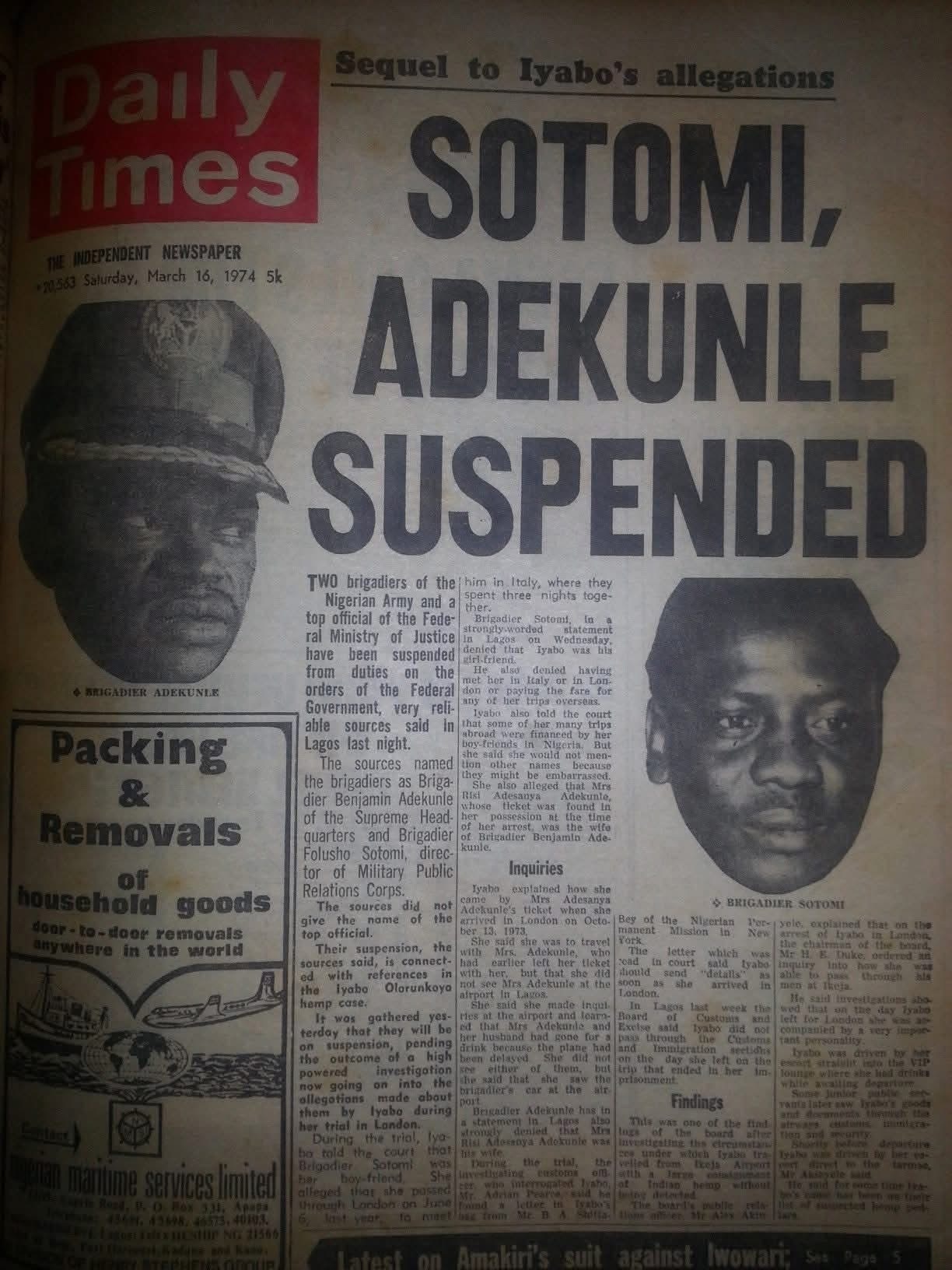

In a major story reported by the Daily Times on Saturday, March 16, 1974, two high-ranking Nigerian military officers were suspended pending an investigation into allegations linked to a high-profile court trial in London.

The Officers Involved

The suspended officers were:

Brigadier Benjamin Adekunle, a prominent figure at the Supreme Headquarters.

Brigadier Foluso Sotomi, the Director of the Military Public Relations Corps.

Both men were regarded as influential figures in Nigeria’s military establishment at the time, making the suspension a matter of national attention.

The Allegations

The suspension stemmed from accusations made by Iyabo Olorunkoya, a Nigerian woman facing trial in London for hemp (cannabis) smuggling. During her proceedings, Iyabo implicated the two brigadiers, claiming they were involved in facilitating or being connected to the illegal activities.

The Federal Government of Nigeria responded promptly by ordering a formal investigation, emphasizing the seriousness of the charges and the need to uphold military discipline and public trust.

Investigation and Suspension

The decision to suspend Brigadiers Adekunle and Sotomi was immediate and aimed at preventing any potential interference with the inquiry. Both officers were required to remain inactive in their official duties until the investigation concluded.

The case drew widespread attention in Nigeria, with citizens and media closely following developments. It was considered one of the most significant headlines in the Daily Times, highlighting public concern over military integrity and accountability.

Historical Significance

This event is a notable example of:

The intersection of military authority and legal accountability in Nigeria during the 1970s.

The influence of international legal cases on domestic affairs, as the accusations arose during a trial in London.

The role of the press in documenting high-profile cases and informing public opinion.

Source

Daily Times, Saturday, March 16, 1974 – Front page headline: “SOTOMI, ADEKUNLE SUSPENDED”

This case remains a significant reference point in Nigerian military history, illustrating the scrutiny and accountability demanded of top officers during politically sensitive periods.

Columns

General Philip Effiong: The Man Who Brought the Nigerian Civil War to an End

General Philip Ifiodu Effiong occupies a pivotal place in Nigerian history as the final Head of State of the defunct Republic of Biafra and the man who formally ended the Nigerian Civil War in January 1970. Though often overshadowed by more prominent figures of the conflict, Effiong’s decision to surrender rather than prolong the war saved countless lives and shaped Nigeria’s post-war trajectory.

Early Life and Military Formation

Philip Ifiodu Effiong was born on January 1, 1925, in Ibiono Ibom, in present-day Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. He joined the Nigerian Army during the colonial period and received professional military training in England, reflecting the British structure of Nigeria’s armed forces at the time. His training and exposure abroad contributed to his reputation as a disciplined, methodical, and principled officer.

Rise During a Time of National Crisis

Nigeria’s First Republic collapsed following political instability and military coups in 1966. When the Eastern Region seceded in May 1967 to form the Republic of Biafra, Effiong aligned with the new state and rose to become one of its most senior military officers. He was appointed Chief of General Staff and Vice Head of State, serving directly under General Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu.

Throughout the war (1967–1970), Effiong was deeply involved in Biafra’s military administration and strategy. As the conflict intensified, Biafra faced severe shortages of food, weapons, and international support, leading to one of the worst humanitarian crises in African history.

Head of State and the Decision to Surrender

By January 1970, Biafra’s military situation had become hopeless. Ojukwu departed for exile in Côte d’Ivoire and handed over authority to Effiong. As Head of State, Effiong inherited a collapsing army and a starving civilian population.

On January 15, 1970, Philip Effiong made the historic decision to surrender Biafra to the Federal Military Government of Nigeria. In a broadcast to the nation, he declared the end of hostilities and appealed for reconciliation and unity. He subsequently led a delegation to Lagos, where he formally handed over to General Yakubu Gowon, marking the official end of the civil war.

His action aligned with Gowon’s post-war policy of “No Victor, No Vanquished,” which sought to reintegrate former Biafrans into Nigeria rather than pursue mass retribution.

Life After the War

Following the war, Effiong lived a largely quiet and private life. Like many former Biafran officials, he faced social and economic difficulties in the immediate post-war years but avoided public political engagement. He did not attempt to leverage his wartime position for personal power or recognition.

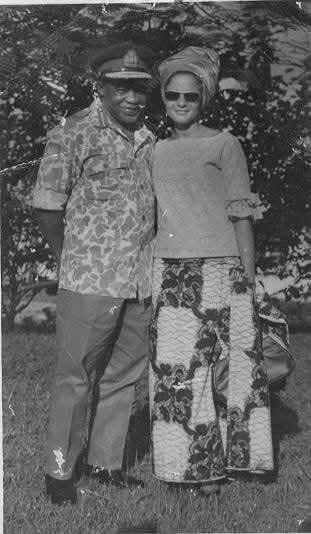

Family and Personal Life

General Effiong was married to Judith Effiong, a Hungarian-born woman whom he met while studying in England. Their marriage, uncommon for the period, attracted attention and reportedly subjected the family to social challenges, particularly after the war. Both Philip and Judith endured significant personal hardship due to his role in Biafra, yet they remained steadfast.

Death and Historical Legacy

Philip Effiong died on November 6, 2003, at the age of 78. Today, he is remembered less as a battlefield commander and more as a leader who demonstrated moral restraint at a critical moment. His decision to surrender rather than fight a futile final stand stands as one of the most consequential acts of leadership in Nigerian history.

General Philip Effiong’s legacy lies in his choice of humanity over hubris, making him the man who closed one of the darkest chapters in Nigeria’s national story.

Sources

Effiong, P. I. Nigeria and Biafra: My Story.

Gowon, Yakubu. The Nigerian Civil War and National Unity.

Stremlau, John J. The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War.

Madiebo, Alexander A. The Nigerian Revolution and the Biafran War.

Nigerian National Archives and contemporary newspaper reports (1967–1970).

Columns

The Aburi Conference of 1967 and the Constitutional Crisis of the Nigerian Federation

In early January 1967, Nigeria was standing at a dangerous crossroads. Less than seven years after independence, the country was already deeply fractured by political rivalry, ethnic violence, and military intervention in governance. The coups of 1966 had destroyed trust among Nigeria’s regions and within the armed forces. It was in this tense atmosphere that Nigerian leaders agreed to meet in Aburi, Ghana, for what would become one of the most important and controversial meetings in the nation’s history.

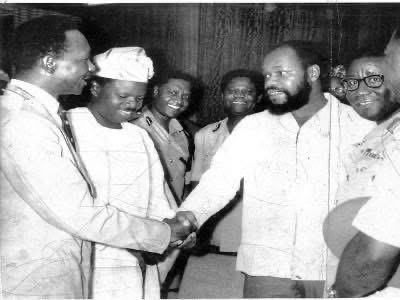

The meeting, held between January 4 and January 5, 1967, brought together the leaders of the Federal Military Government and the regional military governors. The head of the federal government was Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon, while the Eastern Region was represented by its military governor, Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu. Other regional leaders and senior military officers were also present. The goal was simple in theory but difficult in practice. It was to find a peaceful political solution that would keep Nigeria united and prevent the country from sliding into civil war.

Aburi was chosen deliberately as a neutral and calm location outside Nigeria. At the time, Ojukwu insisted that his safety could not be guaranteed anywhere within the country. Ghana, under the leadership of Lieutenant General Joseph Ankrah, offered a peaceful environment where all sides could speak freely without fear. The quiet hill town of Aburi provided a sharp contrast to the tension and uncertainty gripping Nigeria.

The discussions at Aburi were shaped by recent painful experiences. The January 1966 coup had led to the killing of several prominent Northern and Western political leaders, creating resentment and suspicion. The counter coup of July 1966 deepened divisions. By the end of 1966, Nigeria was a country united in name but divided in reality.

At the conference, participants expressed a shared desire to avoid the use of force and to rebuild trust. The outcome of the meeting was a set of resolutions commonly referred to as the Aburi Accord. Central to these agreements was the understanding that the Supreme Military Council would remain the highest authority in the country and that decisions affecting the whole nation should be taken collectively. There was also an emphasis on greater consultation among regions and a recognition of the need to respect regional sensitivities, particularly in matters of security and governance.

Another important aspect of the Aburi discussions was the structure of the Nigerian Army. Given the breakdown of trust within the military after the coups and counter coups, there was agreement that the armed forces needed to be reorganised in a way that reassured all regions. The intention was to prevent any group from feeling dominated or threatened by others. Above all, the spirit of Aburi was one of compromise, dialogue, and the rejection of violence as a solution to political problems.

However, the hope generated at Aburi did not last long. Once the leaders returned to Nigeria, serious disagreements emerged over how the resolutions should be interpreted and implemented. Ojukwu believed that the Aburi Accord granted significant autonomy to the regions and limited the power of the central government. Gowon and other federal officials later argued that while the meeting promoted consultation, it did not dismantle federal authority or turn Nigeria into a loose confederation.

These differing interpretations quickly became a source of conflict. In an attempt to formalise the Aburi resolutions, the Federal Military Government drafted Decree Number 8. Ojukwu rejected this decree, claiming it did not faithfully reflect what had been agreed in Ghana. Trust between the parties collapsed further, and dialogue gave way to suspicion and hardened positions.

By May 1967, the political crisis had reached a breaking point. Ojukwu declared the Eastern Region an independent state known as the Republic of Biafra, citing the failure of the federal government to protect Easterners and honour the Aburi agreements. The federal government rejected the secession, and by July 1967, Nigeria was at war with itself. The Nigerian Civil War would last until January 1970 and result in immense human suffering and loss of life.

Today, the Aburi Conference is remembered as Nigeria’s last serious attempt to resolve its internal crisis through dialogue before the outbreak of war. Historians often describe it as a moment filled with both promise and tragedy. It demonstrated that Nigerian leaders were capable of sitting together to seek peace, yet it also exposed the dangers of vague agreements, mutual distrust, and weak mechanisms for implementation.

The legacy of Aburi continues to shape discussions about federalism, national unity, and conflict resolution in Nigeria. It stands as a reminder that peace requires not only dialogue, but also clarity, sincerity, and a shared commitment to implementation. More than half a century later, the lessons of Aburi remain deeply relevant to Nigeria’s ongoing journey as a diverse and complex nation.

Columns

Meet the only police officer who ever sued Obasanjo

Inspector Henry Ale is recorded as the only police officer that ever sued former President Olusegun Obasanjo according to a clipping from The Republic newspaper.

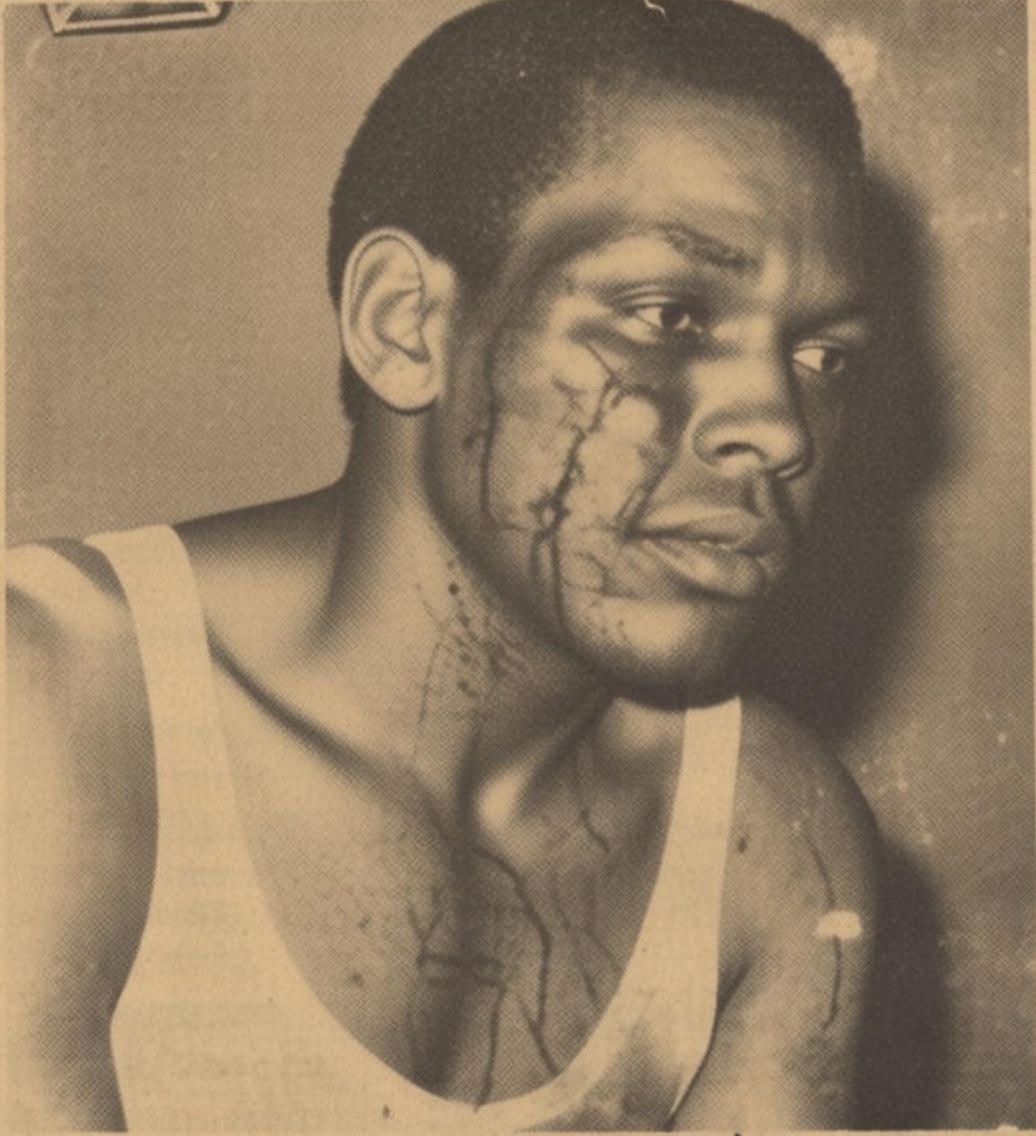

The incident started on December 1, 1988, when the Inspector was said to have stopped the former head of state at a police checkpoint for a routine search.

The report said as a result of this action of his, he was allegedly bundled to Ota, the Ogun State location of Obasanjo farms and reportedly stripped and dealt with. He was said to have lost two teeth and got injured from the incident.

On December 15, that year, Ale engaged the law firm of Chief Gani Fawehinmi to demand ₦250,000 in compensation and an apology, setting a deadline of December 31, 1988. When Obasanjo refused to comply, Ale sued for violation of his fundamental human rights on January 19, 1989 and demanded for ₦600,000.

On July 6, 1989, after several adjournments, the judge, Adewale Oduntan dismissed the lawsuit and, according to Archivi, a historical medium, the judge ruled that only government prosecutors could file cases for violations of fundamental human rights and that Ale’s suit should have been filed as a common law matter.

Credit: Ethnic African Stories

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI