Politics

How did the US economy do under Obama, Trump and Biden?

In the past decade and a half, the US has done incredibly well economically compared to other countries. It added millions of jobs and quickly put the COVID pandemic behind it. Do things need to be “made great” again?

A lot of time, effort and money goes into presidential and national elections in the United States and this year is no exception.

But combing through the data since 2009 shows that no matter who was in power, the economy seemed to be equally driven by global events, demographic developments and decisions made in the White House.

The period from 2009 to 2024 covers both of Barack Obama’s two terms in the White House, plus the single presidential terms of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, which is slowly coming to an end.

Looking back at Obama, Trump and Biden

There were two major disruptors during this time for the economy. The first was the financial crisis that started before Obama took office and the COVID-19 pandemic that struck during Trump’s time in office.

The financial crisis led some to fear the collapse of the entire banking system. Soon afterward GM and Chrysler declared bankrupt to reorganize themselves and the housing market — specifically mortgages — was spinning out of control.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a more immediate impact on the US and global economies. Lockdowns, shortages due to delicate supply chains and the closure of borders caused chaos, deaths and massive job losses.

Partly through large stimulus checks, the US managed to get out of the pandemic slump fast, picking up where the economy left off, creating a strong recovery.

American GDP versus other giants

One problem comparing the impact presidents and their policies make is the lag in time it takes for them to make a difference. Investing in infrastructure or industries like chipmaking is necessary, but the benefits are way in the future. Tightening the border to Mexico may keep out some migrants, but the impact of missing workers takes time to hit supermarket prices.

Another problem is assessing the impact of presidents separately from decisions made together with policymakers in Congress or independent institutions like the Federal Reserve.

Since 1990, American gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has grown each year except 2009 and that was another knock-on effect of the financial crisis. Last year, the country’s GDP per capita was over $81,000 (€74,700).

At the same time, when it comes to the annual percentage of growth per capita, China and India have had stronger growth. Despite this higher growth rate, America’s per capita GDP is still three times higher than China’s and eight times higher than that of India.

In 2023, America’s overall GDP was an astounding $27.36 trillion, making it by far the biggest economy in the world. China came a distant second at $17.66 trillion, followed by Germany and Japan.

A lot of jobs for a lot of people

In the first few months of Obama’s time in office, unemployment went up because of the financial crisis. From April 2009 to September 2011, it was at 9% or more.

After that, it slowly crept down until it reached its lowest level since the 1960s, before a short-lived spike during the COVID-19 pandemic put many out of a job. This year it has hovered around 4%.

On another front, American workers are more productive than others thanks to innovation, spending on research and development, and the willingness of workers to change jobs or move.

Pay inequality at the bottom

Another measure that has increased is pay inequality. America is the most unequal country in the G7 group. The top 1% of Americans hold a huge proportion of the country’s wealth.

In the US, to get into the top 1% of earners requires an annual household income of around $1 million a year before taxes. In the UK it only takes around $250,000.

Company bosses’ pay was over 250 times more than their average employee, wrote Barak Obama in The Economist in October 2016.

Moreover, in 1979 “the top 1% of American families received 7% of all after-tax income. By 2007, that share had more than doubled to 17%,” he wrote. More positively the proportion of people living in extreme poverty fell.

Migration is changing America

The exact number of illegal crossings into the US is hard to measure. Legal migration on the other hand can be counted. One measure of this is the number of green cards granted and from 2009 to 2022 over 14 million people were given such status.

The foreign-born population living in America, legally or otherwise, has grown considerably over the past 50 years in size and share of the population, according to a report issued by the US Census Bureau in April.

In 1970, there were 9.6 million foreign-born residents. By 2022, there were over 46 million, or nearly 14% of the total population.

Of the overall total, nearly one-third of the country’s foreign-born came to the US in 2010 or later and half live in just four states: California, Texas, Florida and New York. More than half have become citizens.

High inflation comes to America

Since January 2009, inflation has gone on a wildride based on the Consumer Price Index.

When Obama took office, inflation was at zero, went into negative territory and eventually climbed to a high of 9.1% in June 2022. This past September, it was down to 2.4%, the lowest since February 2021.

This relatively short period of higher inflation is having a long afterlife and has led to big cost of living increases for many Americans.

Consumer prices are up, and voters are very unhappy about it. It is one of the most important issues this year and could decide the election in swing states. It is also one of the hardest things for any president to control.

Edited by: Uwe Hessler

Author: Timothy Rooks, Rodrigo Menegat Schuinski

Politics

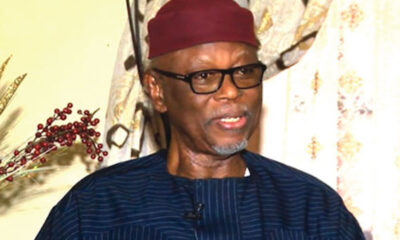

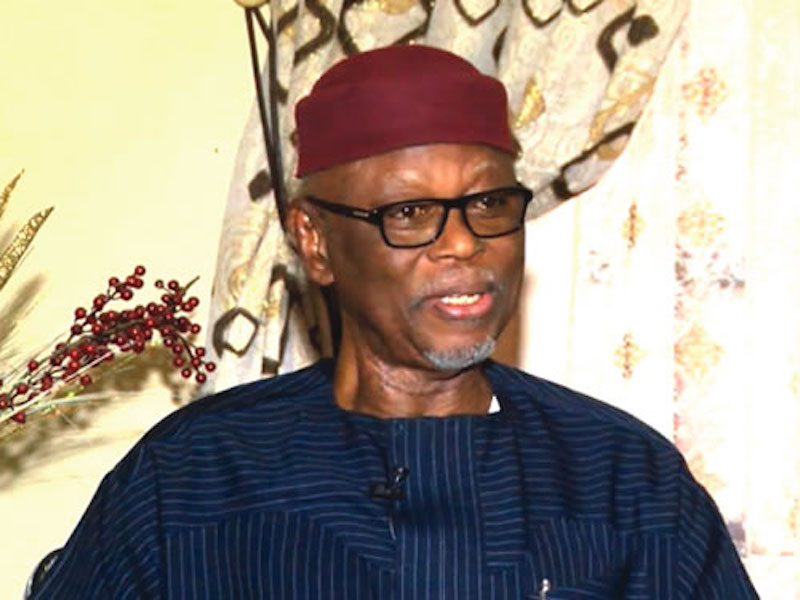

How Buhari shocked me 6 months into his administration – Oyegun

Chairman, Policy Manifesto Committee of the African Democratic Congress, ADC, John Odigie-Oyegun, says former president Muhammadu Buhari gave him the shock of his life, six months into his administration as Nigeria’s leader.

Oyegun made this disclosure on Friday when he featured in an interview on Arise Television’s ‘Prime Time’.

He revealed that as National Chairman of the All Progressives Congress, APC, he went to tell Buhari that he was not delivering his election promises to Nigerians but that the late president told him he would not rule with strictness, but rather wanted to show Nigerians that he is a true civilian president.

The former APC National Chairman lamented that it became business as usual, from there.

“I was national chairman of the APC. Six months or less into our assuming office, fairly alarmed, I went to the late President Buhari for a one-on-one talk. I said Mr President, this is not what the people were expecting. They wanted a bit of the old president Buhari.

“And he explained to me, Mr Chairman, I have learned my lesson. I was shocked. And don’t forget at that time, a lot of prominent Nigerians took their holidays abroad, just to be sure and see what this new sheriff in town will be.

“Buhari told me he wants to now show the people that he’s a true civilian president in Agbada. And by the time we finished the conversation, I said Oh God, we are finished. Because, if he’s not ready to be strict, what’s the point?

“Weeks later, months later, years later, I was proven correct. And of course, it became business as usual, only that they are a new set of tenants in Aso Rock. That was a shocker,” he said.

Politics

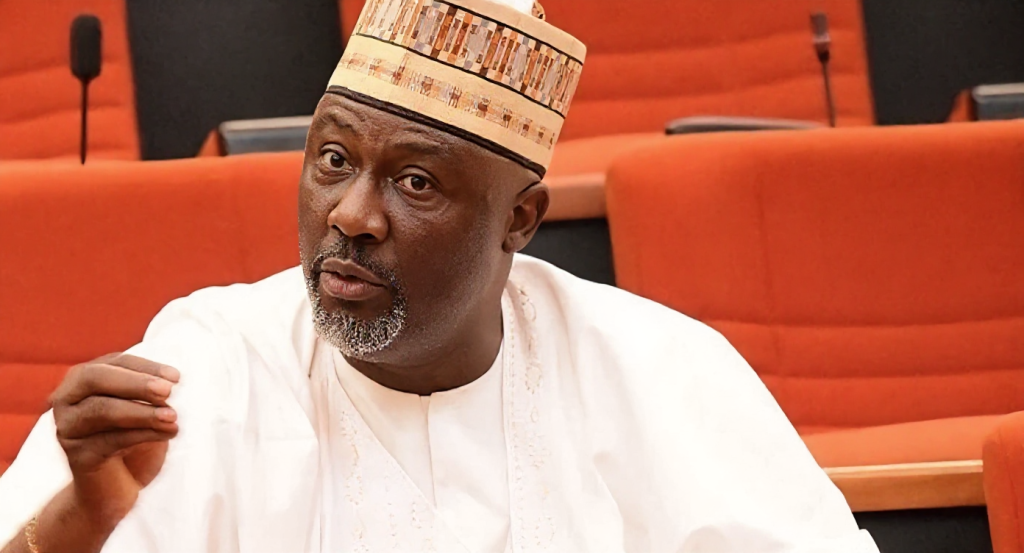

Electoral Reform: Dino alleges senate’s plot to rig 2027 election

Former lawmaker, Dino Melaye Esq, has raised concerns over the Senate’s reported rejection of the electronic transmission of election results.

The move, according to Melaye, is a clear endorsement of election rigging and an indication of a sinister plan to rig the 2027 elections.

In a statement on Friday, the former lawmaker criticized the Senate’s decision, stating that it undermines the credibility of the electoral process.

The African Democratic Congress, ADC chieftain, also stated that the move opens the door for electoral manipulation and fraud.

He further warned that the rejection of electronic transmission of results is a step backwards for democracy in Nigeria.

Melaye called on lawmakers and citizens to stand up against “this blatant attempt to undermine the will of the people and ensure that future elections are free, fair, and transparent”.

Politics

Electoral Act: Nigerians have every reason to be mad at Senate – Ezekwesili

Former Minister of Education, Oby Ezekwesili, has said Nigerians have every reason to be mad at the Senate over the ongoing debate on e-transmission of election results.

Ezekwesili made this known on Friday when she featured in an interview on Arise Television’s ‘Morning Show’ monitored by DAILY POST.

DAILY POST reports that the Senate on Wednesday turned down a proposed change to Clause 60, Subsection 3, of the Electoral Amendment Bill that aimed to compel the electronic transmission of election results.

Reacting to the matter, Ezekwesili said, “The fundamental issue with the review of the Electoral Act is that the Senate retained the INEC 2022 Act, Section 60 Sub 5.

“This section became infamous for the loophole it provided INEC, causing Nigerians to lose trust. Since the law established that it wasn’t mandatory for INEC to transmit electoral results in real-time, there wasn’t much anyone could say.

“Citizens embraced the opportunity to reform the INEC Act, aiming to address ambiguity and discretionary opportunities for INEC. Yet, the Senate handled it with a “let sleeping dogs lie” approach. The citizens have every reason to be as outraged as they currently are.”

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI