Columns

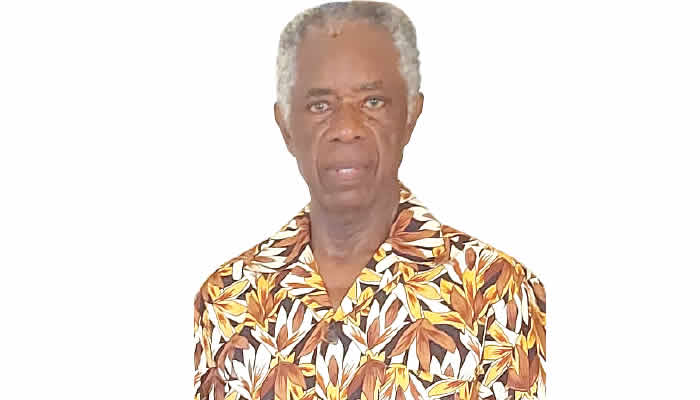

How I flew Buhari around during 1983 coup – 80-year-old ex-Nigeria Airways pilot

Eighty-year-old retired pilot, Captain Jaiyeola Adeola, shares with TEMITOPE ADETUNJI his journey from a carefree childhood to becoming a pioneering Nigerian pilot. He also reflects on his 35 years in aviation, witnessing the rise and fall of Nigeria Airways, changes in the country over time, and other issues

In those days, what was it like growing up as a child compared to now?

Things were easier. We had everything we needed—surplus food, good education, good schools, and security. As children in primary school, we went to school unaccompanied. We played football until dusk, and no one was afraid.

We went to the farm far from town without fear. We were free, we had fun, we had friends, and we were close. Life was peaceful. People didn’t place such emphasis on money as they do now.

Young people today are chasing money and can do anything to get it. Back then, even as kids, we didn’t really care about money. Fruits were free; food was free. We had enough. Maybe two or three pairs of shoes; in fact, most of us went to school barefooted, and it didn’t bother us.

Material things didn’t mean much. What we had was contentment. We were happy and had a very good childhood. We were raised in church, and the Christian upbringing was quite strict.

They could read and write Yoruba fluently but were not formally taught English.

What values did they instill in you that helped shape your life?

Discipline; that was the main thing. We weren’t allowed to misbehave. Of course, we were pampered and had everything we needed, so there was no reason to steal or misbehave. The Christian discipline was strict. You couldn’t just leave the house without informing your parents, and you couldn’t stay out too long without facing punishment.

We had responsibilities from the age of 10. We had to wash all the kitchen utensils, clean the house, and sweep designated areas before going to school. We woke up as early as 6 a.m. to do our chores. We were taught responsibility.

I read about you and saw that you were referred to as a captain. Is that correct?

Yes, back then, the government was well-administered and transparent. After technical school, I got my first job with Guinness in 1965 as an electrical technician.

It was while working there that I saw an advert in the newspaper for aircraft pilot training. I applied and sat the exam. The exam was conducted by a division of WAEC named TEDRO (Test Development and Research Organisation).

We had about three stages of the exam in Lagos. Eventually, we were sent to Zaria to what is now known as the Nigerian College of Aviation Technology for the final stage.

We stayed at the college for two weeks, had classes, and were tested. I was fortunate to be selected as one of the student pilots. At that time, only 22 students were admitted from across the entire country. I was in Course 3; the school restarted in 1967. I was admitted in 1969. It was a two-year program.

So, what was the process of training like back then?

It was a full-time, two-academic-year course, including theory and practical flying training. We started with small, light aircraft that could take only the instructor and the student. Then we moved on to larger ones that could seat about four passengers and two pilots.

Those aircraft had two engines. The final qualification required us to take the UK Civil Aviation Authority exams. A UK check pilot was sent to test us in flying. That was how we obtained our commercial pilot licenses.

At what age did you become a pilot?

I was 26.

Nigeria Airways used to be a symbol of national pride. As someone who rose to the position of General Manager for West Africa, how would you describe its golden years?

I graduated from Zaria in 1971 and worked as a flying instructor until 1976.

Then I joined Nigeria Airways in 1976 as a co-pilot and became a captain in 1981.

I was appointed General Manager Operations for West Africa, the ECOWAS region, and served for some years. It was an extra appointment while I was still flying. I remained a captain until the president shut down Nigeria Airways.

What can you say about the closure of Nigeria Airways?

It was a disaster. Aviation was destroyed in Nigeria; that’s the best way to put it. The airline was operational. When the Federal Government shut down the airline, we pleaded with the president not to. We believed we could keep it going.

The MD at the time, Mr. Abayomi Jones, an excellent manager, came from Lufthansa, where he served as General Manager. After his retirement, he was employed as the Managing Director of Nigeria Airways. He did a great job by keeping the airline afloat.

We appealed to the administration not to shut it down. Mr. Jones even told the government, ‘Don’t give us any money. We don’t need funding from the government. Just leave us alone and let us manage and operate the airline ourselves.’

However, we never really understood what motivated the government. Despite all our pleas and the evidence we provided showing the airline was still functional, he insisted on shutting it down.

So, what was your next move after that happened?

In 2004, I joined ADC Airlines as a captain. While there, I was also appointed Director of Flight Operations for some time. But in 2006, ADC had an accident in Abuja, and the government shut it down.

From there, I joined Capital Airlines as Director of Flight Operations, then left in 2009 to work with Allied Air, a cargo airline, as a project coordinator for their fleet change.

After that, I moved to HAK Air as General Manager. Captain Harrison Kuti brought in five Boeing 737s to start an airline. I left after some months due to disagreements on standards.

I also had the opportunity to serve in the Nigerian Civil Aviation Authority on a two-year renewable contract as Operations Safety Inspector from 2014 to 2016. My contract was not renewed by the DG then, and I left in 2016.

Another opportunity came from Ibom Airlines Limited, and I participated in the certification and launch of the airline as the pioneer Director of Flight Operations until 2021, when I left and decided to retire.

You must have met world leaders, presidents, business moguls, and even military rulers during your time. Do you have any interesting or shocking encounters that you will never forget?

Well, I was a pilot for some of the head of state flights when I worked with Nigeria Airways. I flew as co-pilot when General (Olusegun) Obasanjo went to Khartoum (the capital of Sudan) for an OAU meeting when he was the head of state. I was on the 707 flight to Khartoum.

I also flew General (Muhammadu) Buhari around during the 1983 coup. I remember that for about two or three days, the government hadn’t been formed, and General Buhari, who led the coup, was moving across the country. I was the pilot who flew him around during those three days.

Again, I flew General Ibrahim Babangida to Nairobi when he was head of state. Some of these leaders would sit one-on-one with us in the cockpit and discuss issues concerning Nigeria. They often came into the cockpit to greet us and sometimes stayed for over an hour. I had personal interactions with many of them while working.

Nigeria Airways essentially served as the presidential fleet before an official one was created. Many of these leaders, I would say, didn’t fully understand what nationhood meant. For many of them, leadership was more of an adventure.

Nigeria today seems very different from the country you grew up in. What do you think has changed the most, for better or for worse?

One of the problems I observe today is the collapse of the government secretariat. Back then, you could walk into a Federal Government office and get things done officially. The civil service was efficient and disciplined. Civil service rules were strictly followed.

Today, the secretariat seems to have moved to party headquarters or some hidden office. The same thing applies at the state level. Civil servants no longer play a meaningful role in administration. Everything is centered on the president or the governor. But it is the secretariat that should manage the state, not the governor alone.

That’s a major issue. Politicians have destroyed the civil service. Most workers are now cronies with no interest in actual work. They are inefficient, often unqualified, and not competent enough to manage the portfolios or departments assigned to them.

Now, even processing a document in a government office is a herculean task. You could conduct a survey just by observing the conditions of these offices. Even the furniture and office setup for civil servants are substandard, and so is their condition of service.

Can you describe the feeling of moving or diversifying from electrical engineering to becoming a pilot? What was the experience like?

It was a wonderful experience for me. My earlier technical training involved machines and equipment, so when it came to aircraft, I found it easier to grasp many of the technical aspects. The course was quite difficult, with a very narrow margin for failure.

If you failed a test or didn’t pass a progress check, you would be expelled. Out of the 22 people who started the training in my class, only 12 of us completed it. The rest were expelled for failing tests or underperforming.

How old are you?

I am 80-years-old.

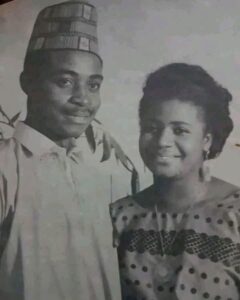

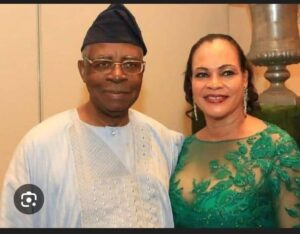

Let’s talk about marriage. You’ve been married for decades. What is the secret to staying together in a world that seems to celebrate divorce and side chicks?

Well, I’ve been married for 52 years now. I believe the issue with many young people today is indiscipline and intolerance. Also, the influence of Christian values is not as strong as it used to be. Many people shout, ‘Praise the Lord’ without truly living by the teachings of Christianity. If you love someone, you wouldn’t want to hurt them.

If you get married in love, you won’t want to do anything to harm your spouse. Of course, there will be disagreements, but as someone once said, ‘A little argument should not destroy a great friendship.’ Differences of opinion are natural, but they shouldn’t lead to fights. Today, people lack discipline. Discipline is doing the right thing, even when it’s uncomfortable or inconvenient.

How did you meet your wife?

I met my wife through a friend. His girlfriend was in the same school as my wife.

Was it secondary school?

No, it was the Federal School of Radiography in Lagos. They were radiographers. We visited them one day, and among the group, something clicked between my wife and me. Since then, we’ve been together.

What were the things you saw in her that made you feel like ‘yes, she is the one?’

I saw that she cared. She was honest and simple. Our courtship was quite beautiful. We respected each other’s preferences. What she liked, I accepted. What I liked, she tolerated. There was no ‘it must be my way’ attitude.

How long were you in a relationship before getting married?

About 15 months, roughly a year and a half.

You were a man of the skies. Did your career ever cause tension at home, and how did your wife cope with your frequent travels?

That’s one of the things I really appreciate about her. She is wise, strong, and devoted to the family. We also had a close relationship with colleagues and friends, so my absence didn’t lead to loneliness. Plus, we had four boys, so she had her hands full. She was also working, so she was busy.

So, what can you say is the secret to your marriage?

We love each other and are very close. What worked for us was the decision not to fight over any issue. There is no issue that cannot be resolved. If you must fight, it has to be over something significant. Otherwise, it’s not worth it. We don’t fight.

Do you believe Nigeria can ever return to the kind of country you once knew—disciplined, visionary, and orderly?

The only way Nigeria can return to that path is if Nigerians start telling the truth, even to themselves. Ethnic groups are not truthful with one another. We’ve lived together for too long and are too integrated for any breakup to work without disaster. Intermarriage, shared communities— all of these make the country’s separation unprofitable.

But people are dishonest and selfish. I think we’ve been acting foolishly as a nation. If you allow me to say it, I’ve always seen Nigeria as a paradise that God created and placed us in to flourish and enjoy. Instead, we’re busy tearing at one another viciously and behaving foolishly, and no one is enjoying the paradise.

That’s why I once thought of writing a book, but I couldn’t put it together. The title I had in mind was ‘The Aches and Pains of a Foolish Nation.’

We’re suffering not because Nigeria lacks resources; the country is wealthy and rich in every sense, but because we are not applying science, education, or strategic planning.

If you study what Chief Obafemi Awolowo did, you’ll understand. If every Nigerian had Awolowo’s mindset, Nigeria would be the China of Africa today.

Right now, no one is developing anything. Everything revolves around governors or the president. But the real influencers are the people around them. Unfortunately, they are also part of Nigeria’s biggest problems.

What are the things you are grateful to God for?

There are many things. First and foremost, I flew airplanes for 35 years without a single incident or accident. That kind of safety can only be by the grace of God. It certainly wasn’t by my own power. I’ve always believed that God is the true captain of every flight.

I remember a small poster I came across while serving as a safety officer. It read, ‘If God is your co-pilot, swap seats.’ That message stayed with me.

Whether in aviation or in everyday life, I believe we should all make God the captain of our journey.

We should take the co-pilot seat because if you’re sitting in the captain’s seat, you’re claiming to be in control, but the true power and direction come from Him.

Where is your wife from?

She’s from Warri, Delta State.

As a Yoruba man, what was your family’s initial reaction to your decision to marry a woman from a different ethnic background?

Since I was 20, when I took my first job, no one in my family has had anything to do with the decisions I made, or the life I lived. Not even my brother or parents. I’ve been independent since then. So, I didn’t even have to involve them. Fortunately for me, my wife speaks Yoruba fluently.

At this age, having the privilege to be alive and see your grandchildren, how do you feel?

I feel happy. I speak with them every week, twice a week. There are five of them now. I speak with them quite often.

Are you involved in anything now that you are retired?

I am currently the President of the Alumni Association of the Nigerian College of Aviation Technology, Zaria. I also serve on the Board of Trustees of the Wings Support Family Foundation.

Columns

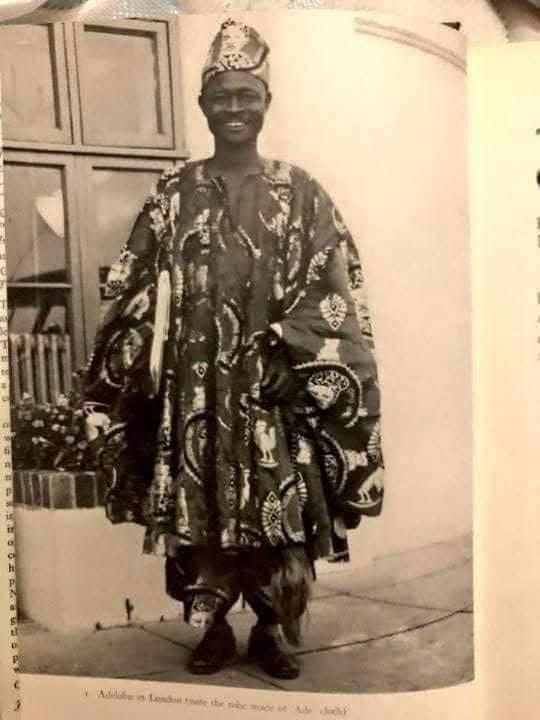

Important Facts About Adegoke Adelabu – “The Lion of the West” (1915–1958)

Full Name: Alhaji Adegoke Gbadamosi Adelabu

Birth Name: Gbadamosi Adegoke Akande

Date of Birth: 3 September 1915

Place of Birth: Ibadan, present-day Oyo State, Nigeria

Nickname: “The Lion of the West” — a title earned for his fearless, combative, and charismatic political style

Education:

St. David’s School, Kudeti, Ibadan (1925–1929)

Government College, Ibadan (from 1936)

Yaba Higher College (admitted on scholarship)

Intellectual Reputation:

Adelabu was renowned for his exceptional oratory, sharp intellect, and ideological boldness, making him one of the most formidable politicians of his generation.

Popular Alias:

Known among his largely non-literate supporters as “Penkelesi” — a Yorubanised version of “peculiar mess”, a phrase he frequently used in speeches, which became inseparably associated with him.

Political Affiliation:

A leading member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) under Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe during the colonial era.

Political Rivalry:

He was a fierce and ideological opponent of Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the Western Region, making Western Nigerian politics highly competitive and polarized in the 1950s.

Colonial-Era Persecution:

Adelabu is widely regarded as one of the most persecuted opposition politicians of the colonial period, having faced about 18 court cases, many believed to be politically motivated.

Corporate Achievement:

He made history as the first African General Manager of the United Africa Company (UAC), a major British trading firm, marking a significant breakthrough for Africans in colonial corporate leadership.

Death:

Date: 25 March 1958

Place: Ode-Remo, Ijebu Province (present-day Ogun State)

Cause: Fatal motor accident involving his Volkswagen Beetle, alongside a Lebanese business associate and two relatives

Age at Death: 43 years old — two years before Nigeria’s independence

Family:

At the time of his death, Adelabu had 12 wives and 15 children, reflecting the social norms of his era.

Aftermath of Death:

His sudden and tragic death sparked widespread riots and unrest across Ibadan, underscoring his immense popularity and political influence among the masses.

Historical Significance:

Adelabu remains one of the most charismatic, controversial, and intellectually formidable politicians in Nigerian pre-independence history, often remembered as a symbol of radical opposition politics and mass mobilisation.

Source:

Nigerian political history archives

Ibadan colonial-era political records

Biographical accounts on Adegoke Adelabu

Yoruba political history documentation

Columns

Pentecostal Evangel Sparks a Great Revival in Nigeria, 1930s

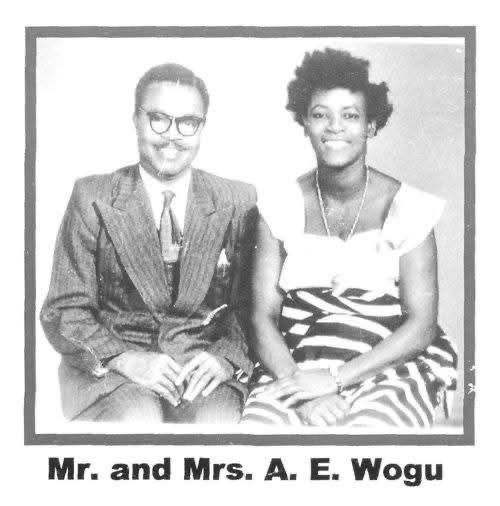

The pioneering role of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu in the rise of indigenous Pentecostalism

The explosive growth of Pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria during the twentieth century did not emerge overnight. Long before megachurches, crusade grounds, and global ministries, the movement was shaped by small prayer groups, radical faith, and indigenous leaders who believed that Christianity in Africa must be spiritually vibrant and culturally rooted. Among the most influential of these pioneers were Mr and Mrs Augustus Ehurie Wogu, whose quiet but profound work in Eastern Nigeria helped spark what later became one of the most significant religious revivals in Nigerian history.

By the 1930s, Nigeria was already experiencing religious ferment. Dissatisfaction with mission churches, hunger for spiritual power, and the search for an African-led Christian expression created fertile ground for Pentecostal ideas. It was within this context that the Wogus emerged as key catalysts of renewal.

Augustus Ehurie Wogu: Faith and Public Life

Augustus Ehurie Wogu (A. E. Wogu) was not a cleric by training. He was a respected civil servant, educated and deeply rooted in Christian discipline. Like many early revivalists, his spiritual influence came not from formal ordination but from conviction, prayer, and leadership within lay Christian circles.

At a time when colonial society often separated public service from spiritual enthusiasm, Wogu embodied both. His faith was intense, practical, and unapologetically Spirit-filled. He believed that Christianity should be marked by holiness, prayer, divine healing, and the active presence of the Holy Spirit—beliefs that resonated deeply with many Nigerians who felt constrained by the formality of mission Christianity.

The Pentecostal Spark: Print, Prayer, and Providence

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Nigerian Pentecostal revival was how it was ignited. Rather than beginning with foreign missionaries, the movement was sparked through printed Pentecostal literature.

In the early 1930s, Wogu and other like-minded believers encountered Pentecostal Evangel, a magazine published by the Assemblies of God in the United States. The publication circulated testimonies of revival, Spirit baptism, divine healing, and missionary zeal. For Wogu and his associates, this literature provided language and theological grounding for experiences they were already seeking.

Inspired, they began intense prayer meetings, fasting, and Bible study sessions in their homes. These gatherings soon attracted others hungry for deeper spiritual life.

The Wogu Home as a Revival Centre

The home of Mr and Mrs Wogu in Umuahia, present-day Abia State, became one of the earliest hubs of Spirit-filled Christianity in Eastern Nigeria. It functioned as:

A prayer house

A teaching centre

A refuge for believers seeking healing and renewal

These meetings were marked by fervent prayer, testimonies, and an emphasis on personal holiness. Importantly, leadership was indigenous. Nigerians taught, prayed, interpreted scripture, and organised fellowships without missionary supervision.

This approach helped dismantle the idea that spiritual authority had to come from Europe or America.

Mrs Wogu and the Role of Women in Early Pentecostalism

While historical narratives often foreground male leaders, Mrs Wogu played a crucial role in sustaining and expanding the revival. She provided spiritual support, hospitality, organisational stability, and mentorship—functions that were essential to the survival of early Pentecostal fellowships.

Her partnership with her husband reflected a pattern later seen across Nigerian Pentecostalism, where women played powerful but often understated roles as prayer leaders, organisers, and spiritual anchors.

From Fellowship to Movement: Birth of Assemblies of God Nigeria

As the revival grew, correspondence began between Nigerian believers and the Assemblies of God in the United States. This relationship eventually led to the arrival of American missionaries in the late 1930s.

Crucially, because the movement already existed before foreign involvement, the resulting church developed with a strong indigenous identity. This distinguished Assemblies of God in Nigeria from many earlier mission-founded churches.

The values emphasised by Wogu and his peers—local leadership, spiritual experience, and African agency—became foundational to the denomination’s growth.

Impact on Nigerian Christianity

The legacy of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu extends far beyond Umuahia or the Assemblies of God denomination. Their work helped shape:

The broader Pentecostal and Charismatic movement in Nigeria

The idea that revival could emerge from African initiative

The theology of prayer, healing, and Spirit baptism that dominates Nigerian Christianity today

Many of Nigeria’s most influential pastors and evangelists trace their spiritual heritage, directly or indirectly, to the revival culture of the 1930s.

A Lasting Legacy

A photograph dated 29 March 1959, showing Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu, captures not just a couple but a generation of believers whose faith reshaped Nigeria’s religious landscape. By that time, the movement they helped ignite had grown beyond imagination.

Their story reminds us that history is often made not only by those on pulpits or platforms, but by faithful individuals who open their homes, pray persistently, and dare to believe that renewal is possible.

Sources

This Week in AG History

Assemblies of God Nigeria historical archives

Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction

J. D. Y. Peel, Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba (contextual reference)

Nigerian church

Columns

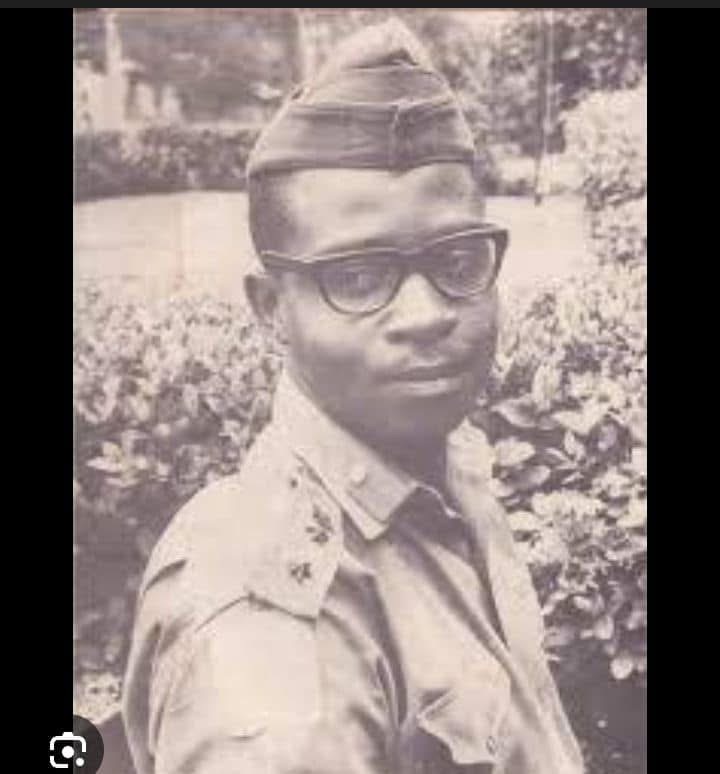

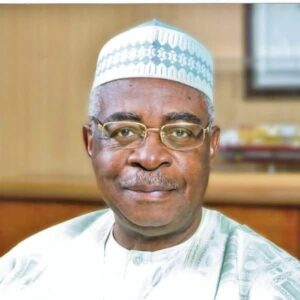

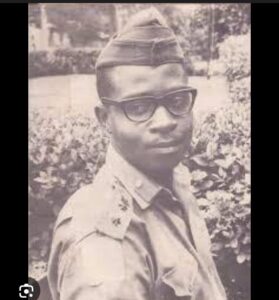

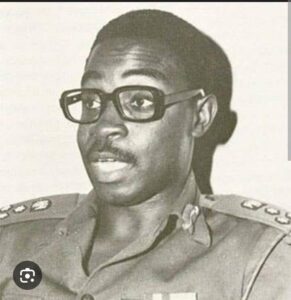

Theophilus danjuma

Lieutenant General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma GCON ) is a retired Nigerian @rmy officer, billionaire businessman, and prominent philanthropist. He is considered one of Nigeria’s most influential and controversial milit@ry figures, having played a central role in several key events in the country’s post-independence history.

Born in Takum, Taraba State on December 9, 1938 , from a humble farming family.

He Attended St. Bartholomew’s Primary School and Benue Provincial Secondary School.

He received a scholarship to study history at Ahmadu Bello University but joined the Nigerian Army in 1960, the year Nigeria gained independence.

Commissioned in 1960, he served as a platoon commander in the Congo Crisîs and rose to the rank of Captain by 1966.

He is widely recognized for leading the troops that arrested and overthrew the first military Head of State, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, during the July 1966 counter-coup.

He served as the Chief of @rmy Staff from 1975 to 1979 under the milit@ry göverñmëñts of Murtala Muhammed and Olusegun Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democratic era, he served as Nigeria’s Minister of D£fence from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democr@tic era, he served as Nigeria’s Ministēr of Defēñce from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

Following his military retirement in 1979, Danjuma became one of Africa’s wealthiest individuals through ventures in shipping and petroleum.

He owns NAL-Comet Group, A leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

Owns NAL-Comet Group, leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

South Atlantic Petroleum (SAPETRO): An oil exploration company with major interests in Nigeria and across Africa.

In 2009,he established TY Danjuma Foundation: with a $100 milliøn grant, it supports education, healthcare, and pôverty alleviation projects throughout Nigeria.

As of early 2026, he remains an active elder statesman, having celebrated his 88th birthday in December 2025.

He continues to be a vocal crìtic of Nigeria’s security situation, recently urging citizens to “rise up and DEFĒÑD themselves” against b@nditry and in$urgēncy when gøvernmēñt protection f@ils.

He remains a “towering national figure” in Taraba State, where he has recently toured ongoing construction for the T.Y. Danjuma University and Academy.

Danjuma is celebrated as a figure who transitioned from milit@ry leadership to business and philanthropy, significantly impacting Nigeria’s development.

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI