Columns

Independence House: Nigeria’s First Skyscraper and a Monument to Freedom in Lagos

A British gift to mark Nigeria’s independence, the iconic 25-storey building in Lagos stands as a symbol of national pride and modern ambition

In the bustling district of Onikan, Lagos, stands one of Nigeria’s most iconic post-independence landmarks — the Independence House. Towering above its surroundings, this 25-storey structure was once a proud symbol of Nigeria’s newfound sovereignty and a mark of its modern aspirations at the dawn of independence.

A Gift from Britain to a New Nation

The Independence House was constructed in 1960 as a gift from the British government to commemorate Nigeria’s independence. The gesture was meant to symbolise the transfer of political power and friendship between the newly independent African nation and its former colonial ruler.

Located west of Tafawa Balewa Square in Onikan, the skyscraper was designed to be a visual representation of progress and self-governance — a bold statement that Nigeria was ready to rise on the global stage.

Nigeria’s First Skyscraper

At the time of its completion, Independence House held the distinction of being the tallest building in Lagos and one of the most advanced structures in West Africa. Its sleek, modernist design stood in sharp contrast to the low colonial-style buildings that surrounded it.

Standing 103 metres (338 feet) tall with 25 floors, the building quickly became a symbol of architectural and economic progress. It marked the beginning of a new era — one in which Nigeria aimed to showcase not just its political independence, but also its capacity for modern development.

Defence House and Its Government Role

In the years following independence, the building became the headquarters for the Federal Ministry of Defence and was popularly referred to as the Defence House. It was a strategic administrative hub, housing key government offices and serving as a focal point for national operations.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, Independence House stood as a symbol of authority and federal presence in Lagos, then Nigeria’s capital. The building’s significance went beyond architecture — it represented national unity and the confidence of a country charting its own path.

The 1993 Fire and Decline

In 1993, a devastating fire broke out in the building, damaging several upper floors. The incident marked the beginning of the building’s decline. Since then, it has remained largely unused and in disrepair, with only occasional discussions about its renovation or repurposing.

Despite its current state, Independence House continues to hold deep historical and emotional value for many Nigerians. It stands as a reminder of a time of optimism, when independence was new and the promise of progress filled the air.

A Legacy of National Pride

Even in its faded glory, the Independence House remains a powerful emblem of Nigeria’s history. Its location near Tafawa Balewa Square, where the nation’s flag was first raised in 1960, ties it to the most defining moment in Nigerian history.

Architecturally, it remains one of the most recognisable examples of mid-20th-century modernism in West Africa. Historically, it serves as a bridge between colonial legacy and post-independence ambition.

For historians and architects alike, the building is a reminder of how infrastructure can embody a nation’s identity and aspirations.

Preservation Efforts and Future Prospects

In recent years, there have been calls from historians, urban planners, and the Lagos State Government to restore Independence House to its former glory. Plans for rehabilitation have been discussed, with proposals to convert it into a heritage site, museum, or cultural centre celebrating Nigeria’s journey to independence.

While no major restoration has yet taken place, Independence House remains an enduring symbol of Lagos’s skyline and Nigeria’s spirit of resilience and progress.

References:

The Guardian Nigeria (2018). Independence House: A Symbol of National Heritage.

Daily Times Nigeria (1960). Britain Presents Independence House to Nigeria.

Federal Ministry of Information and Culture (2015). Monuments of Nigeria’s Independence.

National Archives, Lagos (1960–1993). Records on the Ministry of Defence and Federal Buildings.

Columns

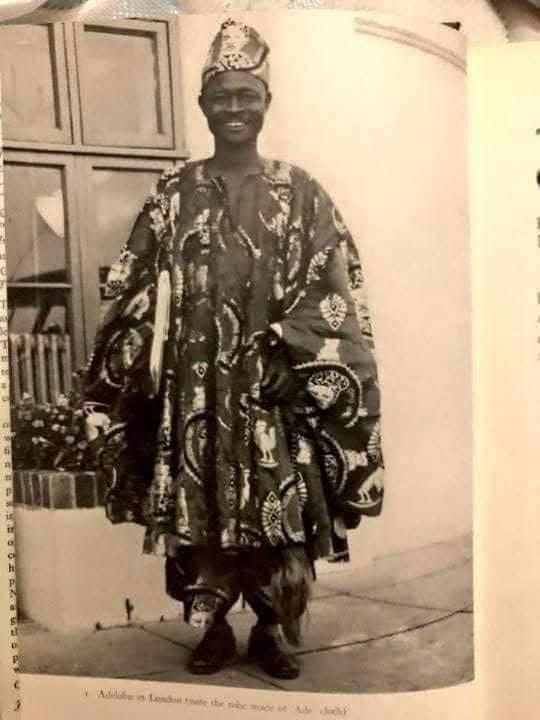

Important Facts About Adegoke Adelabu – “The Lion of the West” (1915–1958)

Full Name: Alhaji Adegoke Gbadamosi Adelabu

Birth Name: Gbadamosi Adegoke Akande

Date of Birth: 3 September 1915

Place of Birth: Ibadan, present-day Oyo State, Nigeria

Nickname: “The Lion of the West” — a title earned for his fearless, combative, and charismatic political style

Education:

St. David’s School, Kudeti, Ibadan (1925–1929)

Government College, Ibadan (from 1936)

Yaba Higher College (admitted on scholarship)

Intellectual Reputation:

Adelabu was renowned for his exceptional oratory, sharp intellect, and ideological boldness, making him one of the most formidable politicians of his generation.

Popular Alias:

Known among his largely non-literate supporters as “Penkelesi” — a Yorubanised version of “peculiar mess”, a phrase he frequently used in speeches, which became inseparably associated with him.

Political Affiliation:

A leading member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) under Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe during the colonial era.

Political Rivalry:

He was a fierce and ideological opponent of Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the Western Region, making Western Nigerian politics highly competitive and polarized in the 1950s.

Colonial-Era Persecution:

Adelabu is widely regarded as one of the most persecuted opposition politicians of the colonial period, having faced about 18 court cases, many believed to be politically motivated.

Corporate Achievement:

He made history as the first African General Manager of the United Africa Company (UAC), a major British trading firm, marking a significant breakthrough for Africans in colonial corporate leadership.

Death:

Date: 25 March 1958

Place: Ode-Remo, Ijebu Province (present-day Ogun State)

Cause: Fatal motor accident involving his Volkswagen Beetle, alongside a Lebanese business associate and two relatives

Age at Death: 43 years old — two years before Nigeria’s independence

Family:

At the time of his death, Adelabu had 12 wives and 15 children, reflecting the social norms of his era.

Aftermath of Death:

His sudden and tragic death sparked widespread riots and unrest across Ibadan, underscoring his immense popularity and political influence among the masses.

Historical Significance:

Adelabu remains one of the most charismatic, controversial, and intellectually formidable politicians in Nigerian pre-independence history, often remembered as a symbol of radical opposition politics and mass mobilisation.

Source:

Nigerian political history archives

Ibadan colonial-era political records

Biographical accounts on Adegoke Adelabu

Yoruba political history documentation

Columns

Pentecostal Evangel Sparks a Great Revival in Nigeria, 1930s

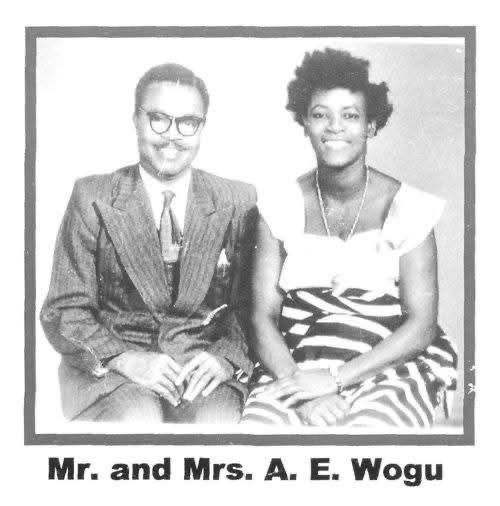

The pioneering role of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu in the rise of indigenous Pentecostalism

The explosive growth of Pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria during the twentieth century did not emerge overnight. Long before megachurches, crusade grounds, and global ministries, the movement was shaped by small prayer groups, radical faith, and indigenous leaders who believed that Christianity in Africa must be spiritually vibrant and culturally rooted. Among the most influential of these pioneers were Mr and Mrs Augustus Ehurie Wogu, whose quiet but profound work in Eastern Nigeria helped spark what later became one of the most significant religious revivals in Nigerian history.

By the 1930s, Nigeria was already experiencing religious ferment. Dissatisfaction with mission churches, hunger for spiritual power, and the search for an African-led Christian expression created fertile ground for Pentecostal ideas. It was within this context that the Wogus emerged as key catalysts of renewal.

Augustus Ehurie Wogu: Faith and Public Life

Augustus Ehurie Wogu (A. E. Wogu) was not a cleric by training. He was a respected civil servant, educated and deeply rooted in Christian discipline. Like many early revivalists, his spiritual influence came not from formal ordination but from conviction, prayer, and leadership within lay Christian circles.

At a time when colonial society often separated public service from spiritual enthusiasm, Wogu embodied both. His faith was intense, practical, and unapologetically Spirit-filled. He believed that Christianity should be marked by holiness, prayer, divine healing, and the active presence of the Holy Spirit—beliefs that resonated deeply with many Nigerians who felt constrained by the formality of mission Christianity.

The Pentecostal Spark: Print, Prayer, and Providence

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Nigerian Pentecostal revival was how it was ignited. Rather than beginning with foreign missionaries, the movement was sparked through printed Pentecostal literature.

In the early 1930s, Wogu and other like-minded believers encountered Pentecostal Evangel, a magazine published by the Assemblies of God in the United States. The publication circulated testimonies of revival, Spirit baptism, divine healing, and missionary zeal. For Wogu and his associates, this literature provided language and theological grounding for experiences they were already seeking.

Inspired, they began intense prayer meetings, fasting, and Bible study sessions in their homes. These gatherings soon attracted others hungry for deeper spiritual life.

The Wogu Home as a Revival Centre

The home of Mr and Mrs Wogu in Umuahia, present-day Abia State, became one of the earliest hubs of Spirit-filled Christianity in Eastern Nigeria. It functioned as:

A prayer house

A teaching centre

A refuge for believers seeking healing and renewal

These meetings were marked by fervent prayer, testimonies, and an emphasis on personal holiness. Importantly, leadership was indigenous. Nigerians taught, prayed, interpreted scripture, and organised fellowships without missionary supervision.

This approach helped dismantle the idea that spiritual authority had to come from Europe or America.

Mrs Wogu and the Role of Women in Early Pentecostalism

While historical narratives often foreground male leaders, Mrs Wogu played a crucial role in sustaining and expanding the revival. She provided spiritual support, hospitality, organisational stability, and mentorship—functions that were essential to the survival of early Pentecostal fellowships.

Her partnership with her husband reflected a pattern later seen across Nigerian Pentecostalism, where women played powerful but often understated roles as prayer leaders, organisers, and spiritual anchors.

From Fellowship to Movement: Birth of Assemblies of God Nigeria

As the revival grew, correspondence began between Nigerian believers and the Assemblies of God in the United States. This relationship eventually led to the arrival of American missionaries in the late 1930s.

Crucially, because the movement already existed before foreign involvement, the resulting church developed with a strong indigenous identity. This distinguished Assemblies of God in Nigeria from many earlier mission-founded churches.

The values emphasised by Wogu and his peers—local leadership, spiritual experience, and African agency—became foundational to the denomination’s growth.

Impact on Nigerian Christianity

The legacy of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu extends far beyond Umuahia or the Assemblies of God denomination. Their work helped shape:

The broader Pentecostal and Charismatic movement in Nigeria

The idea that revival could emerge from African initiative

The theology of prayer, healing, and Spirit baptism that dominates Nigerian Christianity today

Many of Nigeria’s most influential pastors and evangelists trace their spiritual heritage, directly or indirectly, to the revival culture of the 1930s.

A Lasting Legacy

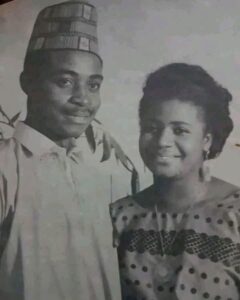

A photograph dated 29 March 1959, showing Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu, captures not just a couple but a generation of believers whose faith reshaped Nigeria’s religious landscape. By that time, the movement they helped ignite had grown beyond imagination.

Their story reminds us that history is often made not only by those on pulpits or platforms, but by faithful individuals who open their homes, pray persistently, and dare to believe that renewal is possible.

Sources

This Week in AG History

Assemblies of God Nigeria historical archives

Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction

J. D. Y. Peel, Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba (contextual reference)

Nigerian church

Columns

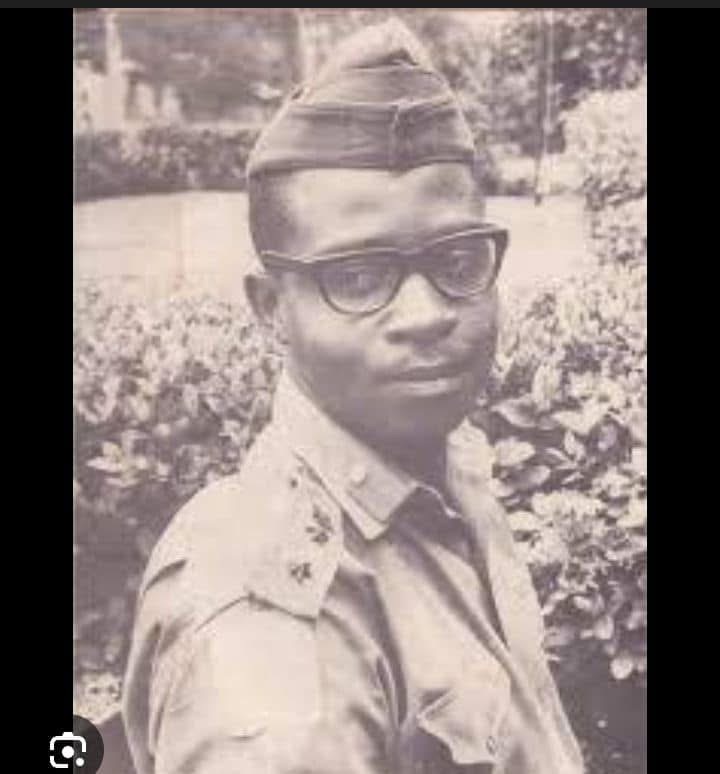

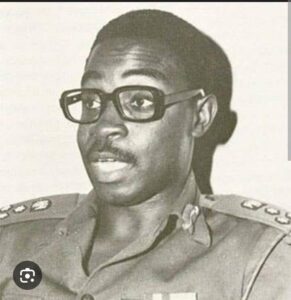

Theophilus danjuma

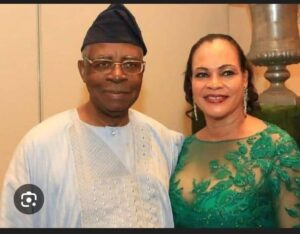

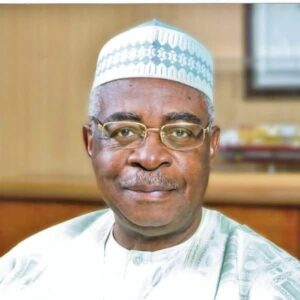

Lieutenant General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma GCON ) is a retired Nigerian @rmy officer, billionaire businessman, and prominent philanthropist. He is considered one of Nigeria’s most influential and controversial milit@ry figures, having played a central role in several key events in the country’s post-independence history.

Born in Takum, Taraba State on December 9, 1938 , from a humble farming family.

He Attended St. Bartholomew’s Primary School and Benue Provincial Secondary School.

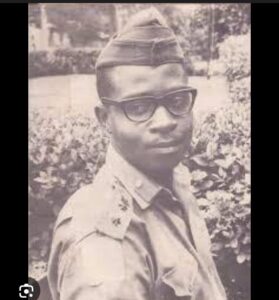

He received a scholarship to study history at Ahmadu Bello University but joined the Nigerian Army in 1960, the year Nigeria gained independence.

Commissioned in 1960, he served as a platoon commander in the Congo Crisîs and rose to the rank of Captain by 1966.

He is widely recognized for leading the troops that arrested and overthrew the first military Head of State, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, during the July 1966 counter-coup.

He served as the Chief of @rmy Staff from 1975 to 1979 under the milit@ry göverñmëñts of Murtala Muhammed and Olusegun Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democratic era, he served as Nigeria’s Minister of D£fence from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democr@tic era, he served as Nigeria’s Ministēr of Defēñce from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

Following his military retirement in 1979, Danjuma became one of Africa’s wealthiest individuals through ventures in shipping and petroleum.

He owns NAL-Comet Group, A leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

Owns NAL-Comet Group, leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

South Atlantic Petroleum (SAPETRO): An oil exploration company with major interests in Nigeria and across Africa.

In 2009,he established TY Danjuma Foundation: with a $100 milliøn grant, it supports education, healthcare, and pôverty alleviation projects throughout Nigeria.

As of early 2026, he remains an active elder statesman, having celebrated his 88th birthday in December 2025.

He continues to be a vocal crìtic of Nigeria’s security situation, recently urging citizens to “rise up and DEFĒÑD themselves” against b@nditry and in$urgēncy when gøvernmēñt protection f@ils.

He remains a “towering national figure” in Taraba State, where he has recently toured ongoing construction for the T.Y. Danjuma University and Academy.

Danjuma is celebrated as a figure who transitioned from milit@ry leadership to business and philanthropy, significantly impacting Nigeria’s development.

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI