Columns

A Reply to Chidi Odinkalu: NJC was unfair to Justice Inyang, JCA by Alex Morgan Esq

After reading the article entitled “Blessed Are The Crooked Judges’ by Prof. Chidi Odinkalu, a legal mind for whom I have nothing but respect, I can’t but agree that the article aptly captures the decisions reached at the 108th Meeting of the National Judiciary Commission (NJC) held on April 29 and 30, 2025.

However, the issues raised in the said article compelled one to do a little more research, and also make some enquiries, on the subject matter. It is based on my findings from these enquiries that, as a lawyer myself, I must disagree with Odinkalu on his inferences and conclusions, especially as they relate to the case of Justice Jane Inyang, JCA. And my areas of disagreement are as follows:

In that article, the highly respected Odinkalu, a former chairman of the Nigerian Human Rights Commission (NHRC), lamented the decay in the nation’s Judiciary and how corrupt judges were daily allowed to get away with hardly a slap on the wrist, recycled and then promoted into even higher offices to continue with their rape of the judiciary, and by extension, the country.

As deep and well-researched as Prof. Odinkalu’s submission is, however, it fell into the trap of not only generalisation, but wrong narrative which the NJC decision appears to have conveyed on the matter, and which the media and public commentators have since latched upon.

And the result? An action that could, at worst, be an honest professional misinterpretation of the law by a judge, was approximated to corruption by those who should, and indeed do, know better. And who have subsequently gone ahead to malign the judex as corrupt.

From his article, Odinkalu also got sold this false narrative that has no basis in the facts of the matter. For the facts of the matter, which actually speak for themselves, would have led to a completely different conclusion if there were no extraneous influences brought to bear on the matter.

On the surface, it accuses Justice Inyang of granting an ex parte order to a receiver manager to sell a property in dispute, even when the matter was still at the interlocutory stage.

But nothing can be farther from the truth. Inyang did not grant an ordinary ex parte order for the sale of the said property. Her order was made alongside other orders in aid of the receivership in line with the provisions of Sections 555 to 563 of the Companies and Allied Matters Act, 2020.

So, to start with, it wa-#s not an illegal order. And court records are replete with precedents of similar orders.

But that is not the only detail the NJC elected to look away from in its dizzying verdict on Justice Inyang.

To begin with, the said order was made on June 14, 2023, in a matter, Suit No. FHC/UY/CS/46/2023, before Justice Inyang at the Federal High Court Uyo Judiciary Division.

Two days later, on June 16, 2023, Justice Inyang’s name was published as a nominee for elevation to the Court of Appeal.

By convention, she was directed to stop sitting and return all files to the Administrative Judge for reassignment. She did just that, effectively taking her hands off the case.

She was not, therefore, in a position to know that her order, which, by the way, was not in finality, was not even served on the Respondent, as she directed.

As every diligent judge handling a receiver manager matter, she granted the order to protect the properties from being destroyed by the debtor, and directed that it be served by publication in a national daily to put everyone on notice.

That service, in fact, is the responsibility of the court bailiff and other court officials, supported by security personnel.

She further adjourned the matter for report of compliance, where all parties, if served would appear before the court to make their respective cases.

That was what was expected of a diligent judge, and was exactly what she did. And two days latter, she was promoted to the Appeal Court.

But the verdict of the NJC and the deliberate media spin and misinterpretation thereof tend to paint the picture that there was something fishy about the ex parte order granted by Justice Inyang. Ironically, what Justice Inyang did is professionally sound, and in keeping with global best practice.

The case which basically arose from a mortgage transaction that went sour, was brought by a Receiver Manager. In matters of this nature, the process is usually to grant an Ex parte order to protect the asset, in this case, Udeme Essiet’s companies, petrol stations and other businesses, from being plundered and dissipated, pending the final determination of the matter.

Since the order was interim, it is usually served on the Respondent, who on receipt files his own case and objections on the adjourned date. On the adjourned date, the court can decide to revoke or vary the interim order. This, Justice Inyang had no opportunity of doing because she had moved on.

The company affected, we hear, is on appeal, which is its right remedy.

But, for the avoidance of doubt, after Justice Inyang made the order, handed over the case file and moved on to assume duty at the Court of Appeal, the Federal High Court system, either by omission or commission, failed to serve the order on the Respondent, while the applicants, the bailiffs and all we went on to sell the said property, using this same temporary order – all these, without the knowledge of Justice Inyang who had since moved on.

We hear that the hearing of the substantive matter of the case, as well as all other related issues is still pending before the same court, while the Respondent has gone on appeal. So, why the hurry to move against Justice Inyang?

Curiously, the case/petition against this alleged offence of Justice Inyang was filed long after the matter had become statute barred. That petition should have been filed within six months of the order, but the petition which the NJC acted upon to indict Justice Inyang came a clear nine months after the said order. This is against NJC’s established regulations.

It gets even curiouser when the buyer of the property in dispute, Justice S. Essien, a judge of the National Industrial Court, who’s not known to Inyang, and who claimed to have bought it for an uncle, was let off the hook, while Inyang was put on trial, using the same facts and evidence. Similarly, neither the court officials, bailiffs, security operatives and all who facilitated this back-door sale was disciplined.

Justice Essien, we gathered, told another panel that he had never met Justice Inyang all his life. That it was, in fact, an uncle of his in the United States of America who saw an auction sales advert and asked him to represent him. He subsequently put in a bid, and was successful. All this while, Justice Inyang was at the Court of Appeal and did not know what was going on.

We gathered that this was why the petitioner apologized to Justice Inyang before the Mary Odili-chaired NJC panel, and withdrew his allegation of bribery, saying that he was now convinced that the order was not induced by any bribe to justice Inyang. In fact, this exchange was actually said to have been recorded by the NJC panel, which still went ahead to indict Inyang.

Even more curious, is the fact that even with the recording of these, the full NJC panel chaired by the CJN still went ahead to uphold the indictment of Justice Inyang, despite that the owner of the said businesses withdrew his allegation of bribery and corruption against Justice Inyang, insisting that the vexatious order was not bribe-induced, and that he only made the accusation out of anger.

In our opinion, once there’s no proof of bribery, corruption and undue influence, the decision of a judge cannot amount to a misconduct. The remedy is appeal.

Our view is that since both the Justice Odili panel and the full panel chaired by the CJN could not establish a case of corruption and bribery against Justice Inyang, the petition should have been struck out or, at the very worst, issue a warning or mild caution.

The NJC’s decisions in this circumstance have done incalculable damage to the name and reputation of Justice Inyang, who, like all of them on the panels, also has a name to protect.

For she has every right to be proud of, and jealously guard, her ancestry. After all, she is the granddaughter of the late Barr. Asuquo Etim Inyang of Ikono Ito, in the Odukpani area of Cross River State. Her grandfather, is the first lawyer from the old Eastern Region (and the South) to be called to bar in both the England and Nigerian. He was admitted to the Inner Temple in 1921 and called to bar in 1924 – in both England and Nigeria.

Of course, it is these and several other inconsistencies between evidence and conclusions that now seem to give grain to the speculations that Justice Inyang may indeed be a victim of conspiracy in high places. For instance, could it be true that Justice Inyang, who was appointed to the Court of Appeal barely two years ago, was not the preferred choice of the establishment? Is this seeming plot to rubbish her part of a bigger plot to take her out and nominate this other preferred judge?

How much of this has got to do with her well known independent and uncompromising stance on several cases where extraneous pressures have allegedly been mounted on judges? For Justice Jane Inyang it was, who gave a dissenting judgment in the Ogun State election petition that upheld Gov. Dapo Abiodun’s election. She had insisted that the Electoral laws were not substantially complied with in the governorship election and had called for a fresh election.

Justice Inyang also delivered the lead judgement which upheld the death sentence passed on Chief Rahman Adedoyin, the Ile-Ife hotelier convicted for the murder, in his hotel, of a post graduate student of the Obafemi Awolowo University who had lodged in the hotel.

Are we now stranded with a judiciary where career progression is directly related to the willingness to bend the rule and comply with the whims of politicians and those who wield political powers?

When did it become a crime for Appeal Court judges to differ on matters involving the ruling party? Must they always tow the official line of protecting persons in office?

Does it mean that the Nigerian judiciary no longer has a place for independent judges who stand by their conviction? Is Justice Inyang now a victim of her independence and impartial interpretation and administration of the law?

Finally how much of Justice Inyang’s travails can be put down to the insinuations of gossips and petty jealously, especially among female judges, whereby judges instigate, sometimes baseless, petitions against fellow judges to get rid of them? Did the recent recognition of Justice Inyang by a national newspaper, and the award that came with that recognition, play any part in winning her new enemies among envious female colleagues?

And, to think of it, why are women oftentimes the biggest obstacles to the advancement of fellow women?

With a woman as Chief Justice of Nigeria, and another woman as President of the Court of Appeal, one would have expected more protection for female judges – or in the least, fair hearing. But the reverse appears to be the case.

This writer recalls that it was also under the CJNship of another woman, Justice Aloma Muktar, that the duo of Justices Glady Olotu and Rita Ajumogobia were unfairly treated and dismissed as judges of the Federal High Court by the same NJC.

Thankfully, the courts would eventually void the decisions of the NJC on these two judges and reinstate them. It is gratifying, therefore, to learn that Justice Inyang has already filed to appeal the decision of the NJC.

But, if indeed the NJC has finally woken up to the yelling need to cleanse the judiciary and the corruption that stinks to high heaven therein, the Justice Jane Inyang case is the wrong place to start from, especially when several judges who have clearly compromised on election petitions and other partisan political matters have been allowed to go scot-free, even as they daily jeopardise Nigeria’s democracy and the country at large.

Wrongfully and mischievously scapegoating Justice Jane Iyang, cannot wipe out the mess. It only worsens it.

Who, for instance, would sanction (or petition against) a certain Kekere-Ekun who sat on the panel that, against all conventional reasoning, awarded the Imo State governorship election to the candidate who finished fourth at the polls? Or a Justice Monica Bolna’an Dongban-Mensem if she is accused, for instance, of having been backed by the local APC establishment to indirectly oversee the curious judicial annihilation of the PDP and its elected officers in her home state of Plateau?

Would these jurists also be the ones who should now sit in judgement over these and other allegations if and when the petitions do come?

To begin with, that several decisions of the NJC have been unable to stand the test of dispassionate interrogation before a competent court calls to question the constitution and the composition of the NJC, as well as the process of arriving at its verdicts. It also calls to question, the idea of allowing serving judges/Justices to sit on the NJC panels, as instances abound whereby these jurists are allowed to sit in judgement over matters in which they have verifiable pecuniary interests. Moreover, it can sometimes be difficult for some serving judges to be completely independent in matters that concern officials of the same government of the day, who are their employers.

It would not be out of place, therefore, to remove the CJN and serving judges from sitting on the NJC and also to thoroughly review and overhaul the powers of the NJC.

Increasingly, the NJC, instead of serving to help maintain the highest level of professionalism among judicial officers, has become a burial ground for some judges to intimidate colleagues and beat them into line whenever they show the slightest sign of independent mindedness.

Yes, this writer may not know Jane Iyang personally, but if her clearly outstanding footprints in the judiciary are anything to go by, it then means that this unmasked injustice against the Justice must not be allowed to stand.

If the NJC has a differing opinion from her understanding and/or interpretation of the law, the petitioner should have been encouraged to appeal the decision – an option that is already being explored. However, to insinuate corruption, and to go ahead and selectively punish the judge for this raises a lot of questions as to ulterior motives. A warning or caution should have sufficed in this instance. However, making it look like a case of corruption is like working towards a predetermined outcome: to indict Inyang by any means possible.

That probably explains why the Justice practically received no protection from the president of the Court of Appeal. Or why the advice of the Chief Judge of the Federal High Court did not appear to have been sought (or not considered) on this matter. For the Federal High Court has the expertise in receiver-manager cases as well as other corporate and commercial complex matters.

Incidentally, this writer believes there is still ample room for the NJC, and the establishment to wriggle themselves out of this messy misadventure. We hear that Justice Inyang’s solicitors, the respected Tayo Oyetibo (SAN) have made a passionate appeal to the CJN for a review of the matter. And we do hope that Justice will finally be served.

Similar, we hope that the respected Prof. Odinkalu now has a truer and better picture to draw a more informed conclusion. The same goes for the general public and other media commentators who have, until now, been fed with the wrong narrative of corruption, bribery and misconduct, even as we wait on the NJC to do the right thing.

*Alex Morgan Esq. lives in Port Harcourt

Columns

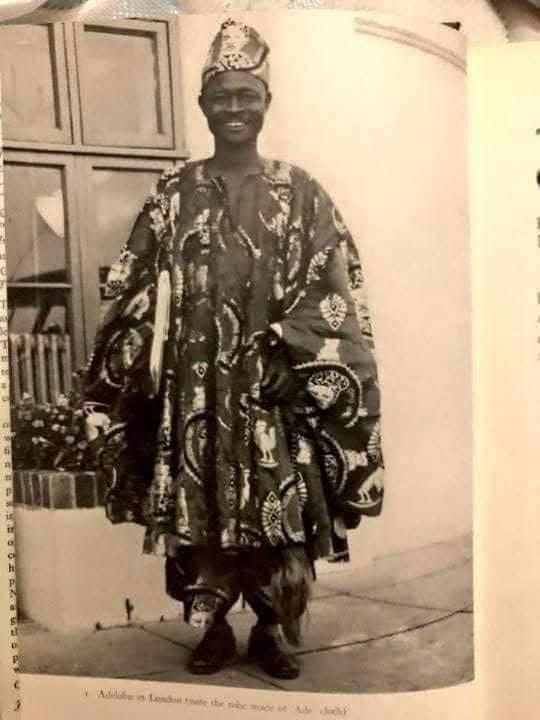

Important Facts About Adegoke Adelabu – “The Lion of the West” (1915–1958)

Full Name: Alhaji Adegoke Gbadamosi Adelabu

Birth Name: Gbadamosi Adegoke Akande

Date of Birth: 3 September 1915

Place of Birth: Ibadan, present-day Oyo State, Nigeria

Nickname: “The Lion of the West” — a title earned for his fearless, combative, and charismatic political style

Education:

St. David’s School, Kudeti, Ibadan (1925–1929)

Government College, Ibadan (from 1936)

Yaba Higher College (admitted on scholarship)

Intellectual Reputation:

Adelabu was renowned for his exceptional oratory, sharp intellect, and ideological boldness, making him one of the most formidable politicians of his generation.

Popular Alias:

Known among his largely non-literate supporters as “Penkelesi” — a Yorubanised version of “peculiar mess”, a phrase he frequently used in speeches, which became inseparably associated with him.

Political Affiliation:

A leading member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) under Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe during the colonial era.

Political Rivalry:

He was a fierce and ideological opponent of Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the Western Region, making Western Nigerian politics highly competitive and polarized in the 1950s.

Colonial-Era Persecution:

Adelabu is widely regarded as one of the most persecuted opposition politicians of the colonial period, having faced about 18 court cases, many believed to be politically motivated.

Corporate Achievement:

He made history as the first African General Manager of the United Africa Company (UAC), a major British trading firm, marking a significant breakthrough for Africans in colonial corporate leadership.

Death:

Date: 25 March 1958

Place: Ode-Remo, Ijebu Province (present-day Ogun State)

Cause: Fatal motor accident involving his Volkswagen Beetle, alongside a Lebanese business associate and two relatives

Age at Death: 43 years old — two years before Nigeria’s independence

Family:

At the time of his death, Adelabu had 12 wives and 15 children, reflecting the social norms of his era.

Aftermath of Death:

His sudden and tragic death sparked widespread riots and unrest across Ibadan, underscoring his immense popularity and political influence among the masses.

Historical Significance:

Adelabu remains one of the most charismatic, controversial, and intellectually formidable politicians in Nigerian pre-independence history, often remembered as a symbol of radical opposition politics and mass mobilisation.

Source:

Nigerian political history archives

Ibadan colonial-era political records

Biographical accounts on Adegoke Adelabu

Yoruba political history documentation

Columns

Pentecostal Evangel Sparks a Great Revival in Nigeria, 1930s

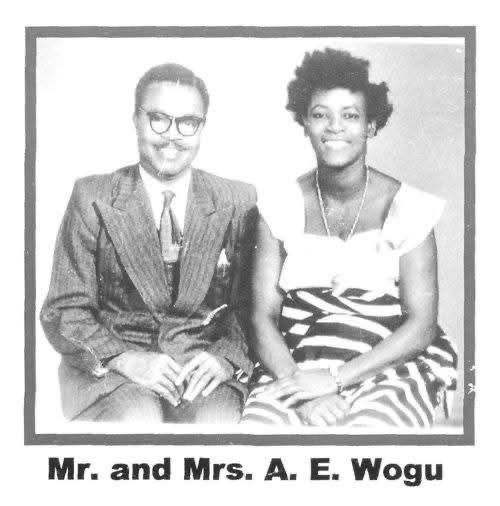

The pioneering role of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu in the rise of indigenous Pentecostalism

The explosive growth of Pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria during the twentieth century did not emerge overnight. Long before megachurches, crusade grounds, and global ministries, the movement was shaped by small prayer groups, radical faith, and indigenous leaders who believed that Christianity in Africa must be spiritually vibrant and culturally rooted. Among the most influential of these pioneers were Mr and Mrs Augustus Ehurie Wogu, whose quiet but profound work in Eastern Nigeria helped spark what later became one of the most significant religious revivals in Nigerian history.

By the 1930s, Nigeria was already experiencing religious ferment. Dissatisfaction with mission churches, hunger for spiritual power, and the search for an African-led Christian expression created fertile ground for Pentecostal ideas. It was within this context that the Wogus emerged as key catalysts of renewal.

Augustus Ehurie Wogu: Faith and Public Life

Augustus Ehurie Wogu (A. E. Wogu) was not a cleric by training. He was a respected civil servant, educated and deeply rooted in Christian discipline. Like many early revivalists, his spiritual influence came not from formal ordination but from conviction, prayer, and leadership within lay Christian circles.

At a time when colonial society often separated public service from spiritual enthusiasm, Wogu embodied both. His faith was intense, practical, and unapologetically Spirit-filled. He believed that Christianity should be marked by holiness, prayer, divine healing, and the active presence of the Holy Spirit—beliefs that resonated deeply with many Nigerians who felt constrained by the formality of mission Christianity.

The Pentecostal Spark: Print, Prayer, and Providence

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Nigerian Pentecostal revival was how it was ignited. Rather than beginning with foreign missionaries, the movement was sparked through printed Pentecostal literature.

In the early 1930s, Wogu and other like-minded believers encountered Pentecostal Evangel, a magazine published by the Assemblies of God in the United States. The publication circulated testimonies of revival, Spirit baptism, divine healing, and missionary zeal. For Wogu and his associates, this literature provided language and theological grounding for experiences they were already seeking.

Inspired, they began intense prayer meetings, fasting, and Bible study sessions in their homes. These gatherings soon attracted others hungry for deeper spiritual life.

The Wogu Home as a Revival Centre

The home of Mr and Mrs Wogu in Umuahia, present-day Abia State, became one of the earliest hubs of Spirit-filled Christianity in Eastern Nigeria. It functioned as:

A prayer house

A teaching centre

A refuge for believers seeking healing and renewal

These meetings were marked by fervent prayer, testimonies, and an emphasis on personal holiness. Importantly, leadership was indigenous. Nigerians taught, prayed, interpreted scripture, and organised fellowships without missionary supervision.

This approach helped dismantle the idea that spiritual authority had to come from Europe or America.

Mrs Wogu and the Role of Women in Early Pentecostalism

While historical narratives often foreground male leaders, Mrs Wogu played a crucial role in sustaining and expanding the revival. She provided spiritual support, hospitality, organisational stability, and mentorship—functions that were essential to the survival of early Pentecostal fellowships.

Her partnership with her husband reflected a pattern later seen across Nigerian Pentecostalism, where women played powerful but often understated roles as prayer leaders, organisers, and spiritual anchors.

From Fellowship to Movement: Birth of Assemblies of God Nigeria

As the revival grew, correspondence began between Nigerian believers and the Assemblies of God in the United States. This relationship eventually led to the arrival of American missionaries in the late 1930s.

Crucially, because the movement already existed before foreign involvement, the resulting church developed with a strong indigenous identity. This distinguished Assemblies of God in Nigeria from many earlier mission-founded churches.

The values emphasised by Wogu and his peers—local leadership, spiritual experience, and African agency—became foundational to the denomination’s growth.

Impact on Nigerian Christianity

The legacy of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu extends far beyond Umuahia or the Assemblies of God denomination. Their work helped shape:

The broader Pentecostal and Charismatic movement in Nigeria

The idea that revival could emerge from African initiative

The theology of prayer, healing, and Spirit baptism that dominates Nigerian Christianity today

Many of Nigeria’s most influential pastors and evangelists trace their spiritual heritage, directly or indirectly, to the revival culture of the 1930s.

A Lasting Legacy

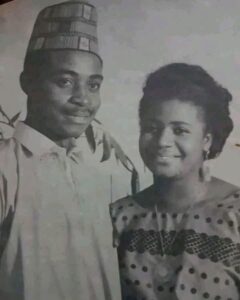

A photograph dated 29 March 1959, showing Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu, captures not just a couple but a generation of believers whose faith reshaped Nigeria’s religious landscape. By that time, the movement they helped ignite had grown beyond imagination.

Their story reminds us that history is often made not only by those on pulpits or platforms, but by faithful individuals who open their homes, pray persistently, and dare to believe that renewal is possible.

Sources

This Week in AG History

Assemblies of God Nigeria historical archives

Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction

J. D. Y. Peel, Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba (contextual reference)

Nigerian church

Columns

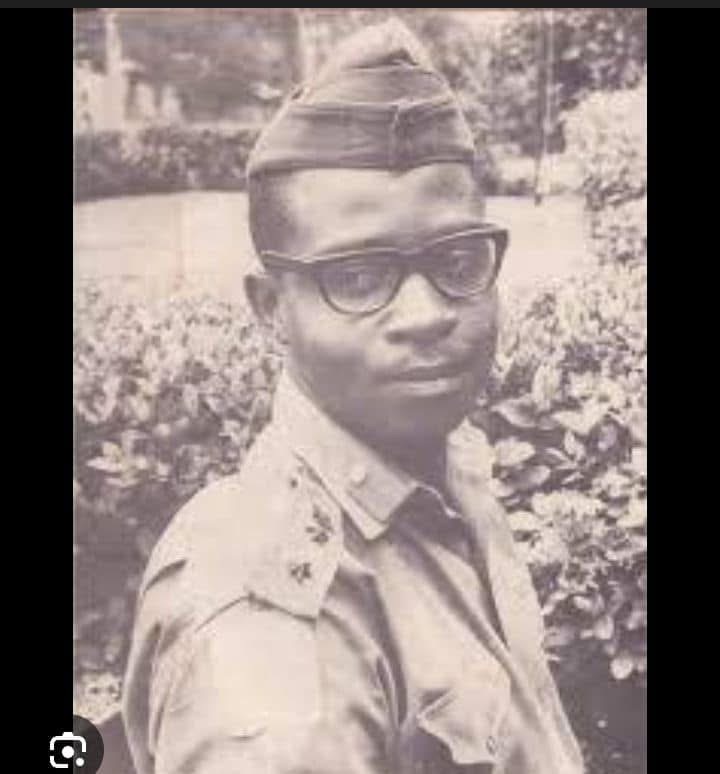

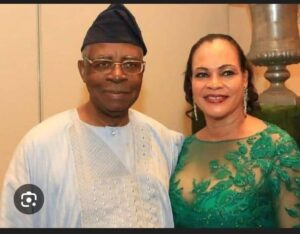

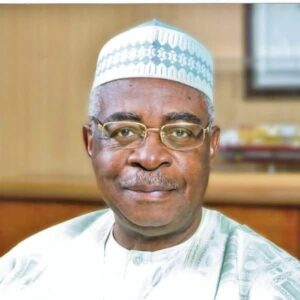

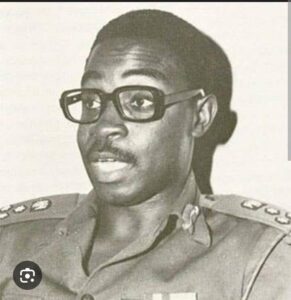

Theophilus danjuma

Lieutenant General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma GCON ) is a retired Nigerian @rmy officer, billionaire businessman, and prominent philanthropist. He is considered one of Nigeria’s most influential and controversial milit@ry figures, having played a central role in several key events in the country’s post-independence history.

Born in Takum, Taraba State on December 9, 1938 , from a humble farming family.

He Attended St. Bartholomew’s Primary School and Benue Provincial Secondary School.

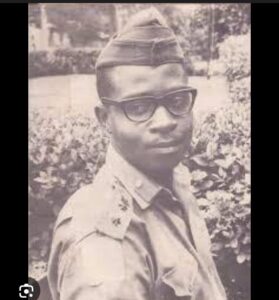

He received a scholarship to study history at Ahmadu Bello University but joined the Nigerian Army in 1960, the year Nigeria gained independence.

Commissioned in 1960, he served as a platoon commander in the Congo Crisîs and rose to the rank of Captain by 1966.

He is widely recognized for leading the troops that arrested and overthrew the first military Head of State, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, during the July 1966 counter-coup.

He served as the Chief of @rmy Staff from 1975 to 1979 under the milit@ry göverñmëñts of Murtala Muhammed and Olusegun Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democratic era, he served as Nigeria’s Minister of D£fence from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democr@tic era, he served as Nigeria’s Ministēr of Defēñce from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

Following his military retirement in 1979, Danjuma became one of Africa’s wealthiest individuals through ventures in shipping and petroleum.

He owns NAL-Comet Group, A leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

Owns NAL-Comet Group, leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

South Atlantic Petroleum (SAPETRO): An oil exploration company with major interests in Nigeria and across Africa.

In 2009,he established TY Danjuma Foundation: with a $100 milliøn grant, it supports education, healthcare, and pôverty alleviation projects throughout Nigeria.

As of early 2026, he remains an active elder statesman, having celebrated his 88th birthday in December 2025.

He continues to be a vocal crìtic of Nigeria’s security situation, recently urging citizens to “rise up and DEFĒÑD themselves” against b@nditry and in$urgēncy when gøvernmēñt protection f@ils.

He remains a “towering national figure” in Taraba State, where he has recently toured ongoing construction for the T.Y. Danjuma University and Academy.

Danjuma is celebrated as a figure who transitioned from milit@ry leadership to business and philanthropy, significantly impacting Nigeria’s development.

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI