Columns

Archaeologists uncover extraordinary 2,000-year-old Roman basilica beneath London office

Archaeologists have made an extraordinary discovery under an office block in London: the remains of the city’s first Roman basilica.

It’s been described as one of the most significant archaeological finds in the capital in recent years.

Dating back nearly 2,000 years to the late 70s or early 80s AD, the basilica was part of the Roman forum – Londinium’s administrative and social hub.

“The significance of this site is that the Roman basilica really was the commercial, social, and economic hub of London,” explains Andrew Henderson-Schwartz, the head of public impact at MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology), in a chat with Euronews Culture.

“It’s where you would go to do big business decisions and big business deals. It’s where you would go to have disputes resolved by a magistrate. It’s where you’d go to have discussions about the kind of decisions that could affect the changes that were happening to both Roman London and and wider Roman Britain.”

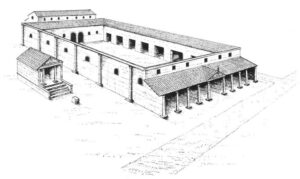

A drawing of a representation of the Roman London Basilica which has been recently unearthed. Credit: Peter Marsden

The developer, Hertshten Properties, which owns the site and holds planning permission for a new office tower, has committed to incorporating the ancient remains into the building’s design and showcasing them in a public visitor centre.

The display is expected to feature a glass floor, allowing visitors to view the basilica’s walls below, and will also include space for food stalls and markets.

“I think it’s important to preserve the past. Obviously, London is a rapidly developing city, and it’s great that we’re growing so quickly with so much development happening. But having these tangible links to the past helps us remember where we came from and gives us a sense of connection to those who came before us,” says Henderson-Schwartz.

With further excavations on the horizon, the archaeological team hopes to answer several questions, such as why the original forum was only used for 20 years before being replaced by a much larger one, which continued to serve the city until the collapse of Roman rule three centuries later.

Columns

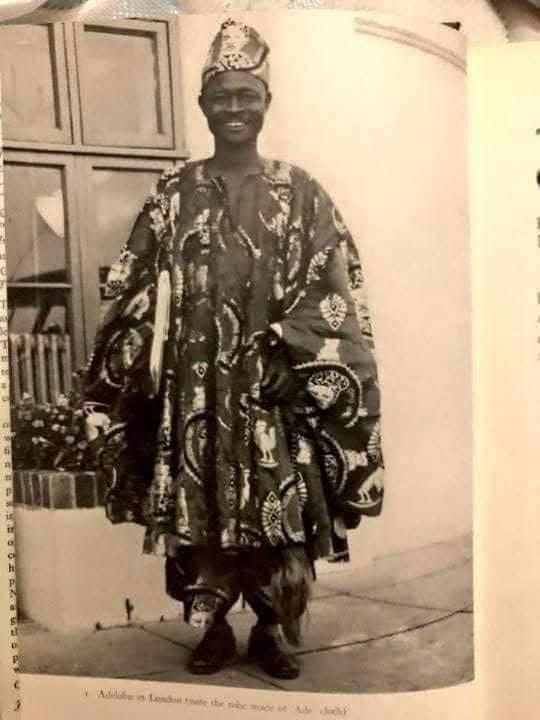

Important Facts About Adegoke Adelabu – “The Lion of the West” (1915–1958)

Full Name: Alhaji Adegoke Gbadamosi Adelabu

Birth Name: Gbadamosi Adegoke Akande

Date of Birth: 3 September 1915

Place of Birth: Ibadan, present-day Oyo State, Nigeria

Nickname: “The Lion of the West” — a title earned for his fearless, combative, and charismatic political style

Education:

St. David’s School, Kudeti, Ibadan (1925–1929)

Government College, Ibadan (from 1936)

Yaba Higher College (admitted on scholarship)

Intellectual Reputation:

Adelabu was renowned for his exceptional oratory, sharp intellect, and ideological boldness, making him one of the most formidable politicians of his generation.

Popular Alias:

Known among his largely non-literate supporters as “Penkelesi” — a Yorubanised version of “peculiar mess”, a phrase he frequently used in speeches, which became inseparably associated with him.

Political Affiliation:

A leading member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) under Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe during the colonial era.

Political Rivalry:

He was a fierce and ideological opponent of Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the Western Region, making Western Nigerian politics highly competitive and polarized in the 1950s.

Colonial-Era Persecution:

Adelabu is widely regarded as one of the most persecuted opposition politicians of the colonial period, having faced about 18 court cases, many believed to be politically motivated.

Corporate Achievement:

He made history as the first African General Manager of the United Africa Company (UAC), a major British trading firm, marking a significant breakthrough for Africans in colonial corporate leadership.

Death:

Date: 25 March 1958

Place: Ode-Remo, Ijebu Province (present-day Ogun State)

Cause: Fatal motor accident involving his Volkswagen Beetle, alongside a Lebanese business associate and two relatives

Age at Death: 43 years old — two years before Nigeria’s independence

Family:

At the time of his death, Adelabu had 12 wives and 15 children, reflecting the social norms of his era.

Aftermath of Death:

His sudden and tragic death sparked widespread riots and unrest across Ibadan, underscoring his immense popularity and political influence among the masses.

Historical Significance:

Adelabu remains one of the most charismatic, controversial, and intellectually formidable politicians in Nigerian pre-independence history, often remembered as a symbol of radical opposition politics and mass mobilisation.

Source:

Nigerian political history archives

Ibadan colonial-era political records

Biographical accounts on Adegoke Adelabu

Yoruba political history documentation

Columns

Pentecostal Evangel Sparks a Great Revival in Nigeria, 1930s

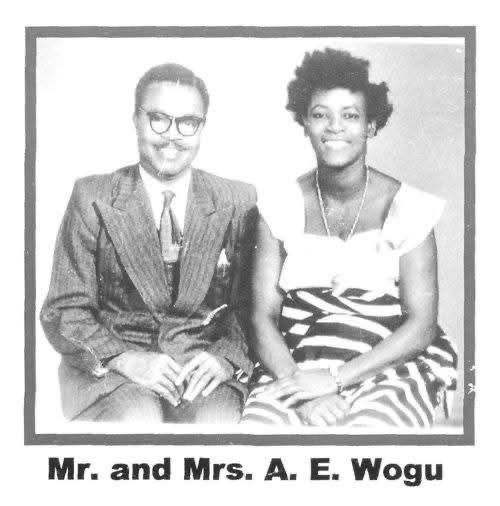

The pioneering role of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu in the rise of indigenous Pentecostalism

The explosive growth of Pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria during the twentieth century did not emerge overnight. Long before megachurches, crusade grounds, and global ministries, the movement was shaped by small prayer groups, radical faith, and indigenous leaders who believed that Christianity in Africa must be spiritually vibrant and culturally rooted. Among the most influential of these pioneers were Mr and Mrs Augustus Ehurie Wogu, whose quiet but profound work in Eastern Nigeria helped spark what later became one of the most significant religious revivals in Nigerian history.

By the 1930s, Nigeria was already experiencing religious ferment. Dissatisfaction with mission churches, hunger for spiritual power, and the search for an African-led Christian expression created fertile ground for Pentecostal ideas. It was within this context that the Wogus emerged as key catalysts of renewal.

Augustus Ehurie Wogu: Faith and Public Life

Augustus Ehurie Wogu (A. E. Wogu) was not a cleric by training. He was a respected civil servant, educated and deeply rooted in Christian discipline. Like many early revivalists, his spiritual influence came not from formal ordination but from conviction, prayer, and leadership within lay Christian circles.

At a time when colonial society often separated public service from spiritual enthusiasm, Wogu embodied both. His faith was intense, practical, and unapologetically Spirit-filled. He believed that Christianity should be marked by holiness, prayer, divine healing, and the active presence of the Holy Spirit—beliefs that resonated deeply with many Nigerians who felt constrained by the formality of mission Christianity.

The Pentecostal Spark: Print, Prayer, and Providence

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Nigerian Pentecostal revival was how it was ignited. Rather than beginning with foreign missionaries, the movement was sparked through printed Pentecostal literature.

In the early 1930s, Wogu and other like-minded believers encountered Pentecostal Evangel, a magazine published by the Assemblies of God in the United States. The publication circulated testimonies of revival, Spirit baptism, divine healing, and missionary zeal. For Wogu and his associates, this literature provided language and theological grounding for experiences they were already seeking.

Inspired, they began intense prayer meetings, fasting, and Bible study sessions in their homes. These gatherings soon attracted others hungry for deeper spiritual life.

The Wogu Home as a Revival Centre

The home of Mr and Mrs Wogu in Umuahia, present-day Abia State, became one of the earliest hubs of Spirit-filled Christianity in Eastern Nigeria. It functioned as:

A prayer house

A teaching centre

A refuge for believers seeking healing and renewal

These meetings were marked by fervent prayer, testimonies, and an emphasis on personal holiness. Importantly, leadership was indigenous. Nigerians taught, prayed, interpreted scripture, and organised fellowships without missionary supervision.

This approach helped dismantle the idea that spiritual authority had to come from Europe or America.

Mrs Wogu and the Role of Women in Early Pentecostalism

While historical narratives often foreground male leaders, Mrs Wogu played a crucial role in sustaining and expanding the revival. She provided spiritual support, hospitality, organisational stability, and mentorship—functions that were essential to the survival of early Pentecostal fellowships.

Her partnership with her husband reflected a pattern later seen across Nigerian Pentecostalism, where women played powerful but often understated roles as prayer leaders, organisers, and spiritual anchors.

From Fellowship to Movement: Birth of Assemblies of God Nigeria

As the revival grew, correspondence began between Nigerian believers and the Assemblies of God in the United States. This relationship eventually led to the arrival of American missionaries in the late 1930s.

Crucially, because the movement already existed before foreign involvement, the resulting church developed with a strong indigenous identity. This distinguished Assemblies of God in Nigeria from many earlier mission-founded churches.

The values emphasised by Wogu and his peers—local leadership, spiritual experience, and African agency—became foundational to the denomination’s growth.

Impact on Nigerian Christianity

The legacy of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu extends far beyond Umuahia or the Assemblies of God denomination. Their work helped shape:

The broader Pentecostal and Charismatic movement in Nigeria

The idea that revival could emerge from African initiative

The theology of prayer, healing, and Spirit baptism that dominates Nigerian Christianity today

Many of Nigeria’s most influential pastors and evangelists trace their spiritual heritage, directly or indirectly, to the revival culture of the 1930s.

A Lasting Legacy

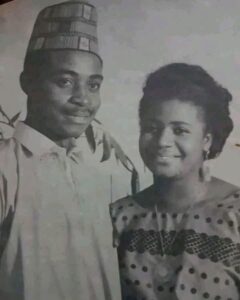

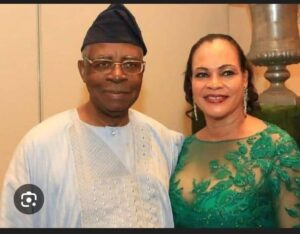

A photograph dated 29 March 1959, showing Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu, captures not just a couple but a generation of believers whose faith reshaped Nigeria’s religious landscape. By that time, the movement they helped ignite had grown beyond imagination.

Their story reminds us that history is often made not only by those on pulpits or platforms, but by faithful individuals who open their homes, pray persistently, and dare to believe that renewal is possible.

Sources

This Week in AG History

Assemblies of God Nigeria historical archives

Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction

J. D. Y. Peel, Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba (contextual reference)

Nigerian church

Columns

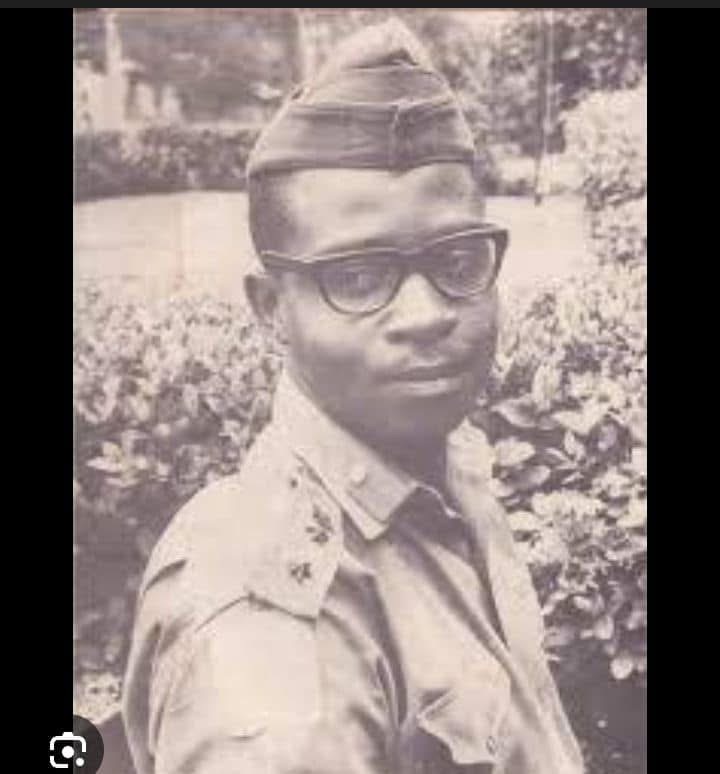

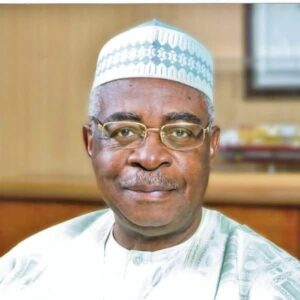

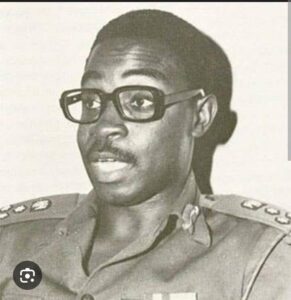

Theophilus danjuma

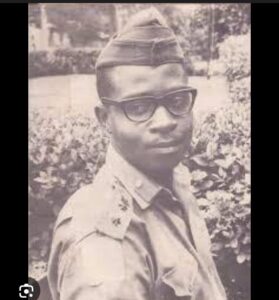

Lieutenant General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma GCON ) is a retired Nigerian @rmy officer, billionaire businessman, and prominent philanthropist. He is considered one of Nigeria’s most influential and controversial milit@ry figures, having played a central role in several key events in the country’s post-independence history.

Born in Takum, Taraba State on December 9, 1938 , from a humble farming family.

He Attended St. Bartholomew’s Primary School and Benue Provincial Secondary School.

He received a scholarship to study history at Ahmadu Bello University but joined the Nigerian Army in 1960, the year Nigeria gained independence.

Commissioned in 1960, he served as a platoon commander in the Congo Crisîs and rose to the rank of Captain by 1966.

He is widely recognized for leading the troops that arrested and overthrew the first military Head of State, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, during the July 1966 counter-coup.

He served as the Chief of @rmy Staff from 1975 to 1979 under the milit@ry göverñmëñts of Murtala Muhammed and Olusegun Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democratic era, he served as Nigeria’s Minister of D£fence from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democr@tic era, he served as Nigeria’s Ministēr of Defēñce from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

Following his military retirement in 1979, Danjuma became one of Africa’s wealthiest individuals through ventures in shipping and petroleum.

He owns NAL-Comet Group, A leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

Owns NAL-Comet Group, leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

South Atlantic Petroleum (SAPETRO): An oil exploration company with major interests in Nigeria and across Africa.

In 2009,he established TY Danjuma Foundation: with a $100 milliøn grant, it supports education, healthcare, and pôverty alleviation projects throughout Nigeria.

As of early 2026, he remains an active elder statesman, having celebrated his 88th birthday in December 2025.

He continues to be a vocal crìtic of Nigeria’s security situation, recently urging citizens to “rise up and DEFĒÑD themselves” against b@nditry and in$urgēncy when gøvernmēñt protection f@ils.

He remains a “towering national figure” in Taraba State, where he has recently toured ongoing construction for the T.Y. Danjuma University and Academy.

Danjuma is celebrated as a figure who transitioned from milit@ry leadership to business and philanthropy, significantly impacting Nigeria’s development.

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI