Columns

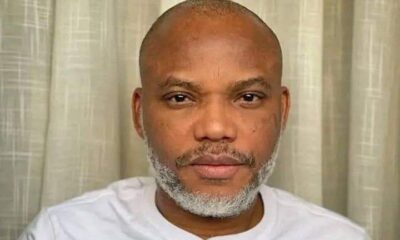

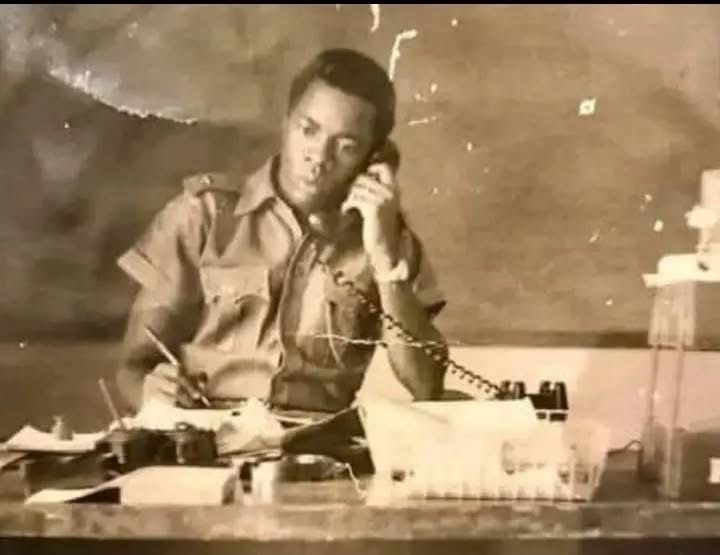

MAJOR DANIEL IDOWU BAMIDELE: THE LOYAL SOLDIER BETRAYED BY THE SYSTEM HE SERVED. UNKNOWN TO BAMIDELE AT THE TIME, BUHARI WAS DEEPLY INVOLVED IN THE PLANNING OF THE COUP HE WAS ATTEMPTING TO ALERT THE ARMY AGAINST.

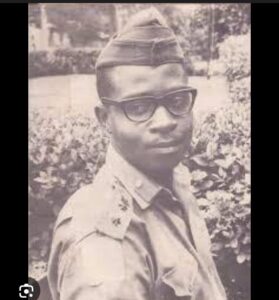

On March 5, 1986, Major Daniel Idowu Bamidele, a brilliant and decorated officer of the Nigerian Army, was executed by firing squad alongside nine other military personnel. His alleged crime was conspiracy to commit treason linked to the popular “Vatsa Coup” against the military regime of General Ibrahim Babangida.

Yet, Bamidele’s story was not that of rebellion, but of a loyal officer punished for remaining silent. His silence was a consequence of an earlier betrayal that had shaken his faith in the very system he served.

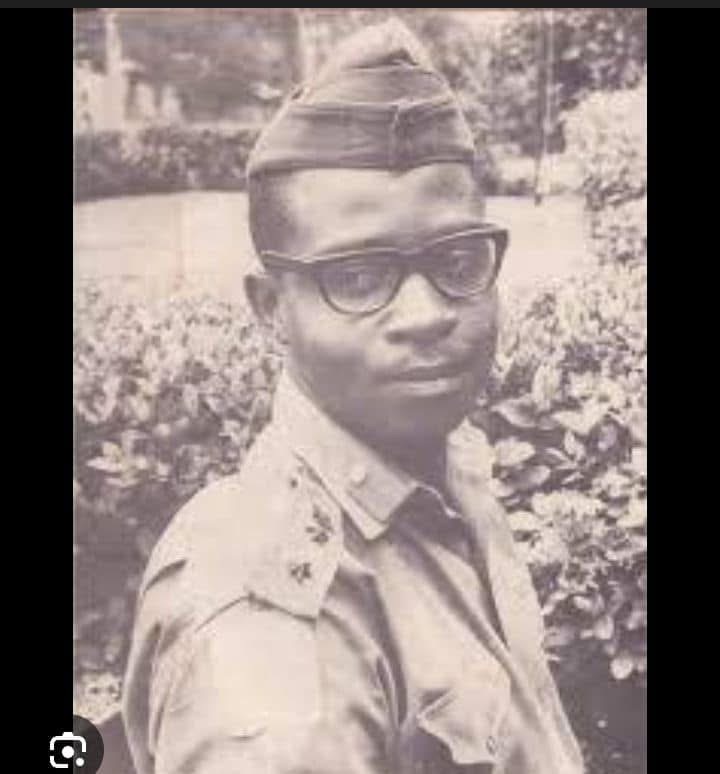

Born in 1949, Bamidele joined the Nigerian Army in 1968 during the height of the Nigerian Civil War. He was initially recruited as a non-commissioned officer and was posted to the 12th Commando Brigade, where he fought under Colonel Benjamin Adekunle and later Colonel Olusegun Obasanjo. His competence and leadership on the battlefield earned him a recommendation for officer training, and he was commissioned into the Nigerian Army on July 29, 1970 after completing training at the Nigerian Defence Academy.

In October 1983, during an official trip to Kaduna to print documents for the Chief of Army Staff Conference, Bamidele overheard rumours of a coup being planned to oust President Shehu Shagari. On returning to Jos, he acted promptly and responsibly by reporting the intelligence to his General Officer Commanding, Major General Muhammadu Buhari. Unknown to Bamidele at the time, Buhari was deeply involved in the planning of the coup he was attempting to alert the army against.

Within days of his report, Bamidele was quietly summoned to Lagos and detained at Tego Barracks by officers of the Directorate of Military Intelligence. He was accused of plotting a coup, the very one he had tried to prevent. Fake witnesses were presented, a mock interrogation was conducted, and false reports were submitted to the National Security Organisation, then under the leadership of Umaru Shinkafi, in an effort to mislead the Shagari government. While the real coup plotters carried on with their plans, Bamidele languished in detention. Eventually, on November 25, 1983, he was released without charge due to the complete absence of evidence against him.

He returned to Jos bewildered by the series of events that had just unfolded. The shocking truth came to light on January 1, 1984 when his former GOC, Major General Muhammadu Buhari whom he had reported the coup plot to announced himself as Nigeria’s new Head of State, having seized power in a military coup, validating everything Bamidele had feared and proving the betrayal he had suffered.

After his experience, Bamidele wisely chose to remain silent about any subsequent coup plots.

In early 1984, Bamidele’s name appeared on a list of officers to be compulsorily retired. When the list was presented to Head of State Buhari for approval, he struck Bamidele’s name off the list, reason unclear, possibly acknowledging the injustice of his prior ordeal. Instead, Bamidele was posted to the Command and Staff College in Jaji as a Directing Staff, where he resumed his duties.

The events that led to his execution began in 1985, following General Babangida’s overthrow of Buhari. Not long after assuming office, Babangida’s intelligence network claimed it had uncovered a plot to remove him from power. At the center of this alleged conspiracy was Major General Mamman Vatsa, Babangida’s childhood friend and then Minister of the Federal Capital Territory. Bamidele was implicated in the conspiracy based on his attendance at a meeting in a guest house in Makurdi. That meeting included other senior officers such as Lieutenant Colonel Michael Iyorshe, Lieutenant Colonel Musa Bitiyong, Lieutenant Colonel Christian Oche, Wing Commander Ben Ekele, and Wing Commander Adamu Sakaba.

Although political discussions and criticisms of the Babangida regime took place during the gathering, there was no evidence of operational coup planning. However, Bamidele, still haunted by his 1983 ordeal, chose to remain silent. It was that silence that became the basis for the charge of conspiracy to commit treason.

He was arrested and tried by a Special Military Tribunal. The trial was conducted in secret, with no right of appeal, and little opportunity for fair defense. Despite the absence of clear evidence linking him to any actual plot, Bamidele was found guilty.

Before he was executed, he delivered a powerful, solemn statement, a statement that has since become one of the most quoted last words in Nigerian military history.

He said:

“I heard of the 1983 coup planning, told my GOC General Buhari who detained me for two weeks in Lagos. Instead of a pat on the back, I received a stab. How then do you expect me to report this one? This trial marks the eclipse of my brilliant and unblemished career of 19 years. I fought in the civil war with the ability it pleased God to give me. It is unfortunate that I’m being convicted for something which I have had to stop on two occasions. This is not self-adulation but a sincere summary of the qualities inherent in me. It is an irony of fate that the president of the tribunal who in 1964 felt that I was good enough to take training in the UK is now saddled with the duty of showing me the exit from the force and the world.”

On March 5, 1986, Major Daniel Idowu Bamidele was executed by firing squad at Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison. Among those executed with him were Major General Mamman Vatsa, Lieutenant Colonel Musa Bitiyong, Lieutenant Colonel Christian Oche, Lieutenant Colonel Clement Akale, Lieutenant Colonel M. Parwang, Wing Commander A.A. Togun, Major A.K. Obasa, Wing Commander Ben Ekele, and Wing Commander Adamu Sakaba.

Major Bamidele’s life and death remain a haunting reminder of the dangers faced by soldiers of conscience. His ordeal reflects the cost of honour in a system where truth was expendable and power was absolute. He was a soldier punished for doing the right thing once, and then punished again for refusing to be used.

Today, his name stands as a symbol of tragic integrity, a man who paid the ultimate price for trusting his superiors and remaining loyal to the oath he swore.

Rest in power, Major Daniel Idowu Bamidele. Nigerians will never forget you.

Columns

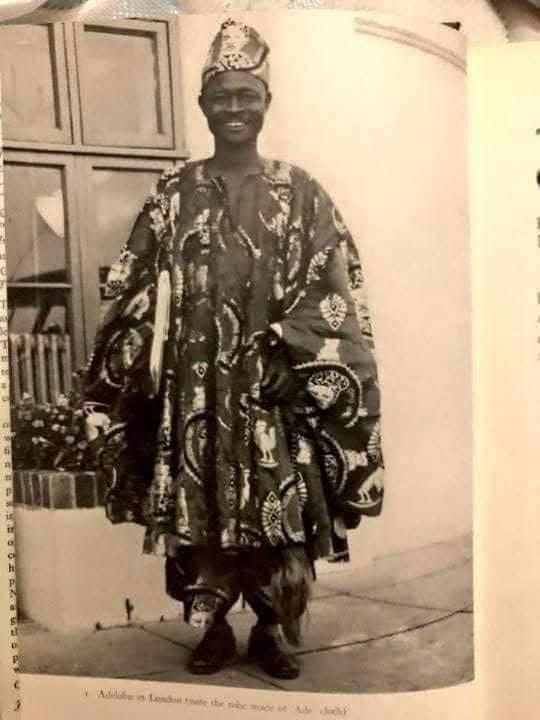

Important Facts About Adegoke Adelabu – “The Lion of the West” (1915–1958)

Full Name: Alhaji Adegoke Gbadamosi Adelabu

Birth Name: Gbadamosi Adegoke Akande

Date of Birth: 3 September 1915

Place of Birth: Ibadan, present-day Oyo State, Nigeria

Nickname: “The Lion of the West” — a title earned for his fearless, combative, and charismatic political style

Education:

St. David’s School, Kudeti, Ibadan (1925–1929)

Government College, Ibadan (from 1936)

Yaba Higher College (admitted on scholarship)

Intellectual Reputation:

Adelabu was renowned for his exceptional oratory, sharp intellect, and ideological boldness, making him one of the most formidable politicians of his generation.

Popular Alias:

Known among his largely non-literate supporters as “Penkelesi” — a Yorubanised version of “peculiar mess”, a phrase he frequently used in speeches, which became inseparably associated with him.

Political Affiliation:

A leading member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) under Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe during the colonial era.

Political Rivalry:

He was a fierce and ideological opponent of Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the Western Region, making Western Nigerian politics highly competitive and polarized in the 1950s.

Colonial-Era Persecution:

Adelabu is widely regarded as one of the most persecuted opposition politicians of the colonial period, having faced about 18 court cases, many believed to be politically motivated.

Corporate Achievement:

He made history as the first African General Manager of the United Africa Company (UAC), a major British trading firm, marking a significant breakthrough for Africans in colonial corporate leadership.

Death:

Date: 25 March 1958

Place: Ode-Remo, Ijebu Province (present-day Ogun State)

Cause: Fatal motor accident involving his Volkswagen Beetle, alongside a Lebanese business associate and two relatives

Age at Death: 43 years old — two years before Nigeria’s independence

Family:

At the time of his death, Adelabu had 12 wives and 15 children, reflecting the social norms of his era.

Aftermath of Death:

His sudden and tragic death sparked widespread riots and unrest across Ibadan, underscoring his immense popularity and political influence among the masses.

Historical Significance:

Adelabu remains one of the most charismatic, controversial, and intellectually formidable politicians in Nigerian pre-independence history, often remembered as a symbol of radical opposition politics and mass mobilisation.

Source:

Nigerian political history archives

Ibadan colonial-era political records

Biographical accounts on Adegoke Adelabu

Yoruba political history documentation

Columns

Pentecostal Evangel Sparks a Great Revival in Nigeria, 1930s

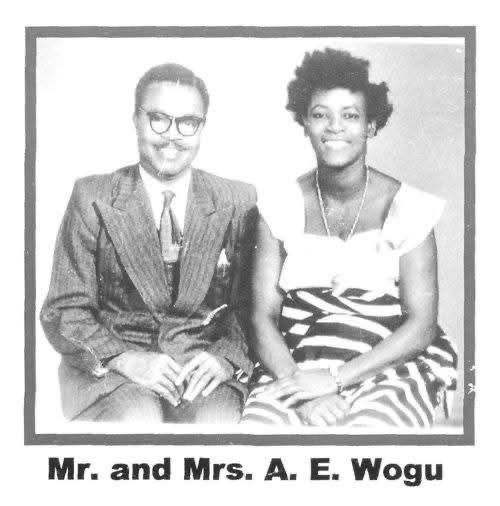

The pioneering role of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu in the rise of indigenous Pentecostalism

The explosive growth of Pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria during the twentieth century did not emerge overnight. Long before megachurches, crusade grounds, and global ministries, the movement was shaped by small prayer groups, radical faith, and indigenous leaders who believed that Christianity in Africa must be spiritually vibrant and culturally rooted. Among the most influential of these pioneers were Mr and Mrs Augustus Ehurie Wogu, whose quiet but profound work in Eastern Nigeria helped spark what later became one of the most significant religious revivals in Nigerian history.

By the 1930s, Nigeria was already experiencing religious ferment. Dissatisfaction with mission churches, hunger for spiritual power, and the search for an African-led Christian expression created fertile ground for Pentecostal ideas. It was within this context that the Wogus emerged as key catalysts of renewal.

Augustus Ehurie Wogu: Faith and Public Life

Augustus Ehurie Wogu (A. E. Wogu) was not a cleric by training. He was a respected civil servant, educated and deeply rooted in Christian discipline. Like many early revivalists, his spiritual influence came not from formal ordination but from conviction, prayer, and leadership within lay Christian circles.

At a time when colonial society often separated public service from spiritual enthusiasm, Wogu embodied both. His faith was intense, practical, and unapologetically Spirit-filled. He believed that Christianity should be marked by holiness, prayer, divine healing, and the active presence of the Holy Spirit—beliefs that resonated deeply with many Nigerians who felt constrained by the formality of mission Christianity.

The Pentecostal Spark: Print, Prayer, and Providence

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Nigerian Pentecostal revival was how it was ignited. Rather than beginning with foreign missionaries, the movement was sparked through printed Pentecostal literature.

In the early 1930s, Wogu and other like-minded believers encountered Pentecostal Evangel, a magazine published by the Assemblies of God in the United States. The publication circulated testimonies of revival, Spirit baptism, divine healing, and missionary zeal. For Wogu and his associates, this literature provided language and theological grounding for experiences they were already seeking.

Inspired, they began intense prayer meetings, fasting, and Bible study sessions in their homes. These gatherings soon attracted others hungry for deeper spiritual life.

The Wogu Home as a Revival Centre

The home of Mr and Mrs Wogu in Umuahia, present-day Abia State, became one of the earliest hubs of Spirit-filled Christianity in Eastern Nigeria. It functioned as:

A prayer house

A teaching centre

A refuge for believers seeking healing and renewal

These meetings were marked by fervent prayer, testimonies, and an emphasis on personal holiness. Importantly, leadership was indigenous. Nigerians taught, prayed, interpreted scripture, and organised fellowships without missionary supervision.

This approach helped dismantle the idea that spiritual authority had to come from Europe or America.

Mrs Wogu and the Role of Women in Early Pentecostalism

While historical narratives often foreground male leaders, Mrs Wogu played a crucial role in sustaining and expanding the revival. She provided spiritual support, hospitality, organisational stability, and mentorship—functions that were essential to the survival of early Pentecostal fellowships.

Her partnership with her husband reflected a pattern later seen across Nigerian Pentecostalism, where women played powerful but often understated roles as prayer leaders, organisers, and spiritual anchors.

From Fellowship to Movement: Birth of Assemblies of God Nigeria

As the revival grew, correspondence began between Nigerian believers and the Assemblies of God in the United States. This relationship eventually led to the arrival of American missionaries in the late 1930s.

Crucially, because the movement already existed before foreign involvement, the resulting church developed with a strong indigenous identity. This distinguished Assemblies of God in Nigeria from many earlier mission-founded churches.

The values emphasised by Wogu and his peers—local leadership, spiritual experience, and African agency—became foundational to the denomination’s growth.

Impact on Nigerian Christianity

The legacy of Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu extends far beyond Umuahia or the Assemblies of God denomination. Their work helped shape:

The broader Pentecostal and Charismatic movement in Nigeria

The idea that revival could emerge from African initiative

The theology of prayer, healing, and Spirit baptism that dominates Nigerian Christianity today

Many of Nigeria’s most influential pastors and evangelists trace their spiritual heritage, directly or indirectly, to the revival culture of the 1930s.

A Lasting Legacy

A photograph dated 29 March 1959, showing Mr and Mrs A. E. Wogu, captures not just a couple but a generation of believers whose faith reshaped Nigeria’s religious landscape. By that time, the movement they helped ignite had grown beyond imagination.

Their story reminds us that history is often made not only by those on pulpits or platforms, but by faithful individuals who open their homes, pray persistently, and dare to believe that renewal is possible.

Sources

This Week in AG History

Assemblies of God Nigeria historical archives

Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction

J. D. Y. Peel, Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba (contextual reference)

Nigerian church

Columns

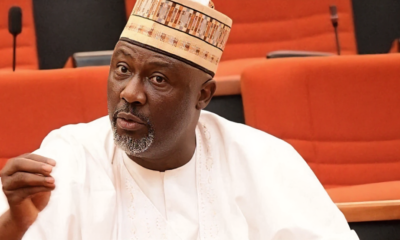

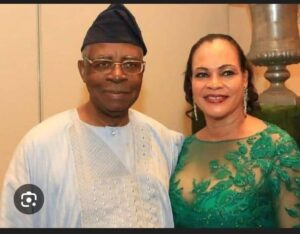

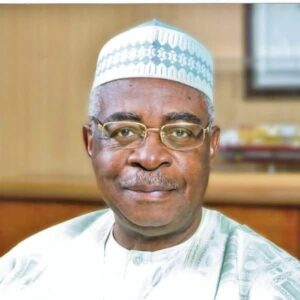

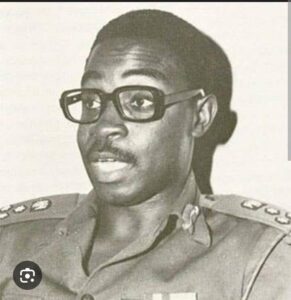

Theophilus danjuma

Lieutenant General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma GCON ) is a retired Nigerian @rmy officer, billionaire businessman, and prominent philanthropist. He is considered one of Nigeria’s most influential and controversial milit@ry figures, having played a central role in several key events in the country’s post-independence history.

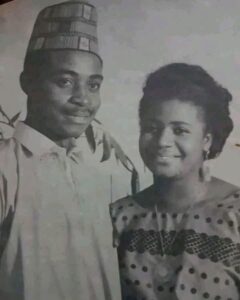

Born in Takum, Taraba State on December 9, 1938 , from a humble farming family.

He Attended St. Bartholomew’s Primary School and Benue Provincial Secondary School.

He received a scholarship to study history at Ahmadu Bello University but joined the Nigerian Army in 1960, the year Nigeria gained independence.

Commissioned in 1960, he served as a platoon commander in the Congo Crisîs and rose to the rank of Captain by 1966.

He is widely recognized for leading the troops that arrested and overthrew the first military Head of State, General Aguiyi-Ironsi, during the July 1966 counter-coup.

He served as the Chief of @rmy Staff from 1975 to 1979 under the milit@ry göverñmëñts of Murtala Muhammed and Olusegun Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democratic era, he served as Nigeria’s Minister of D£fence from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

After returning to public service in the democr@tic era, he served as Nigeria’s Ministēr of Defēñce from 1999 to 2003 under President Obasanjo.

Following his military retirement in 1979, Danjuma became one of Africa’s wealthiest individuals through ventures in shipping and petroleum.

He owns NAL-Comet Group, A leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

Owns NAL-Comet Group, leading indigenous shipping and terminal operator in Nigeria.

South Atlantic Petroleum (SAPETRO): An oil exploration company with major interests in Nigeria and across Africa.

In 2009,he established TY Danjuma Foundation: with a $100 milliøn grant, it supports education, healthcare, and pôverty alleviation projects throughout Nigeria.

As of early 2026, he remains an active elder statesman, having celebrated his 88th birthday in December 2025.

He continues to be a vocal crìtic of Nigeria’s security situation, recently urging citizens to “rise up and DEFĒÑD themselves” against b@nditry and in$urgēncy when gøvernmēñt protection f@ils.

He remains a “towering national figure” in Taraba State, where he has recently toured ongoing construction for the T.Y. Danjuma University and Academy.

Danjuma is celebrated as a figure who transitioned from milit@ry leadership to business and philanthropy, significantly impacting Nigeria’s development.

-

Business1 year ago

US court acquits Air Peace boss, slams Mayfield $4000 fine

-

Trending1 year ago

Trending1 year agoNYA demands release of ‘abducted’ Imo chairman, preaches good governance

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoMexico’s new president causes concern just weeks before the US elections

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoPutin invites 20 world leaders

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoRussia bans imports of agro-products from Kazakhstan after refusal to join BRICS

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky falls ill in police custody, rushed to hospital

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Bobrisky transferred from Immigration to FCID, spends night behind bars

-

Education1 year ago

GOVERNOR FUBARA APPOINTS COUNCIL MEMBERS FOR KEN SARO-WIWA POLYTECHNIC BORI